Rio Earth Summit 1992

33 years after the Rio Earth Summit, what have we learnt?

Context: Thirty-three years after the Rio Earth Summit of 1992, the world continues to grapple with the promises, principles, and paradoxes it set in motion.

What was the significance of the Rio Summit?

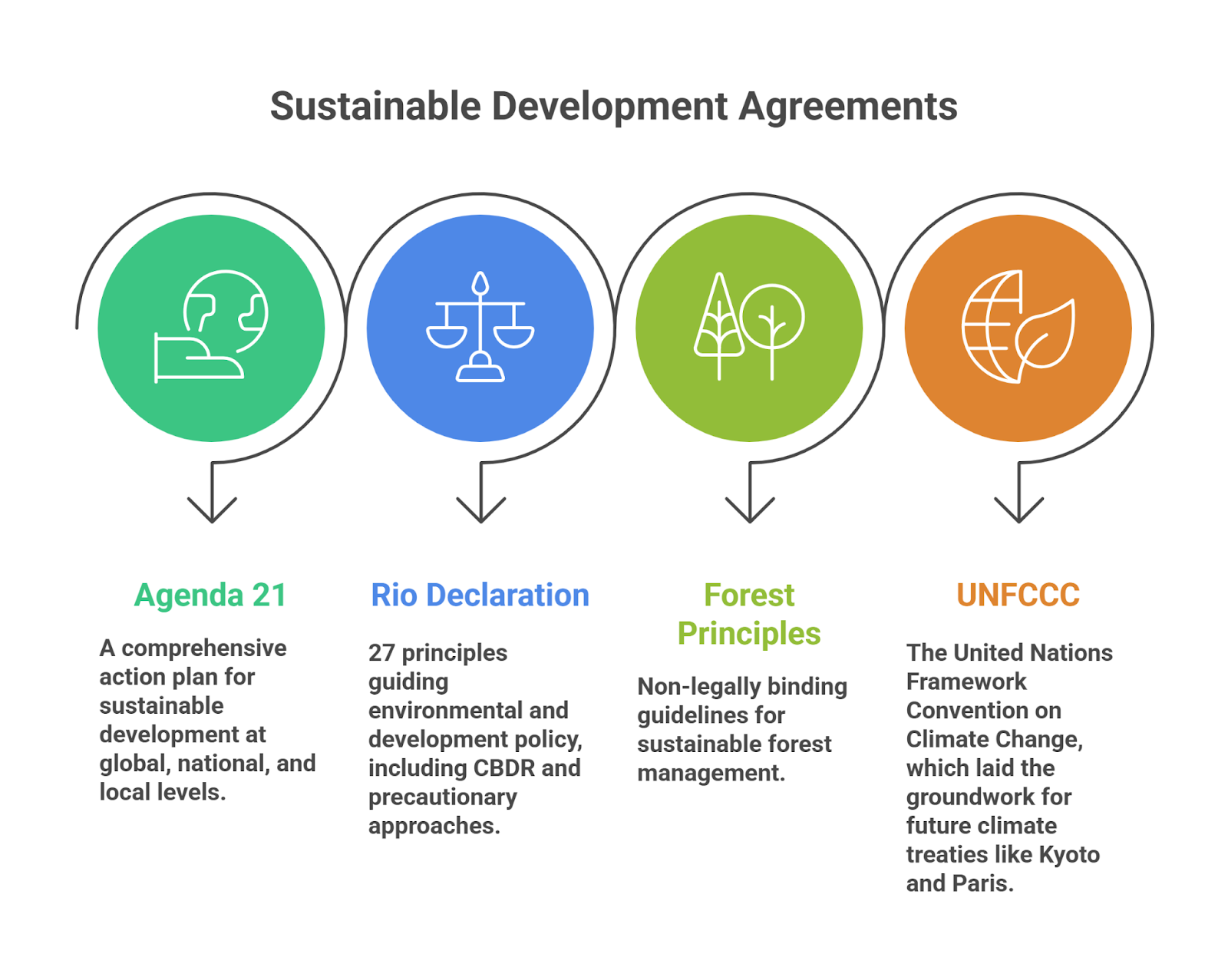

The Rio Earth Summit, officially the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from June 3–14, 1992. It was a watershed moment in global environmental diplomacy.

- It was the first global summit to link environmental protection with economic development, introducing the concept of sustainable development as a universal goal.

- It established the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR), recognising that developed nations bear greater responsibility for environmental degradation.

- It empowered the Global South, especially India and China, to assert their developmental rights while demanding fairness in climate action.

- It laid the groundwork for multilateral environmental treaties and long-term cooperation on climate change, biodiversity, and land degradation.

The summit was attended by 179 countries, 118 heads of state, and thousands of NGOs, scientists, and civil society representatives—making it one of the largest diplomatic gatherings in history.

What are the pending challenges of the Rio Summit?

- Dilution of Equity Principles: The Paris Agreement weakened Rio’s rules-based system, replacing it with voluntary pledges. CBDR has been eroded, blurring lines between historical polluters and emerging economies.

- Failure to Decarbonise: Emissions in the Global North remained high, while manufacturing shifted to the Global South. No binding targets were set at Rio, and subsequent frameworks lacked enforcement.

- Trade vs. Climate: WTO-led trade liberalisation post-Rio sidelined environmental priorities. Export-driven models in the South often compromise ecological integrity.

- Finance and Technology Gaps: The promised $100 billion per year in climate finance remains elusive. Technology transfer has been slow, with IP barriers and geopolitical tensions.

- Global South’s Marginalisation: The South didn’t own the environmental agenda in 1992—it was seen as conditional. Today, there’s a push for “neolocalisation” and contextual green development, but global structures still favour the North.

- Operationalising Equity: Equity must now be embedded in trade, finance, supply chains, and access to capital. Without clear frameworks, multilateralism risks becoming transactional rather than principled.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH