Public Distribution System and Food Deprivation in India

India’s Public Distribution System helps reduce food deprivation but faces issues such as leakages, inefficiencies, and a cereal-centric bias. Explore insights from HCES 2024 and the Thali Index on how to reform PDS for nutrition security, fiscal sustainability, and inclusive growth.

Context

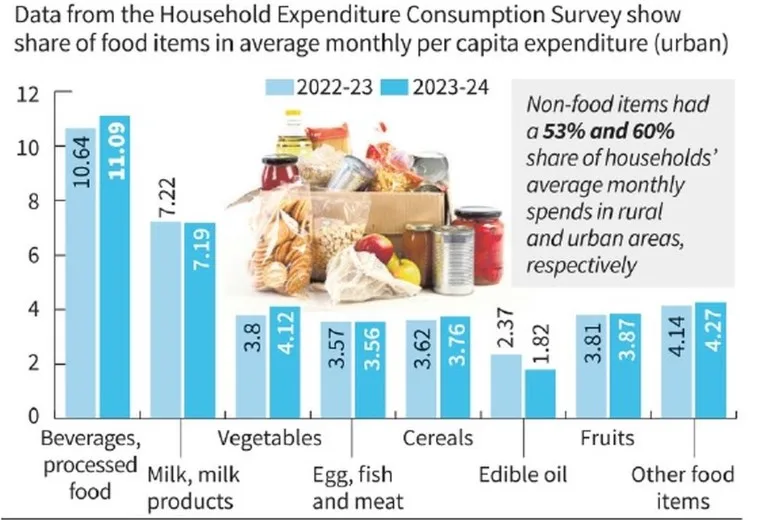

The release of the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2024 has reignited debates around poverty and food deprivation in India. According to the World Bank (2025), extreme poverty in India has fallen to just 2.3%. Yet, alternative approaches suggest a more sobering reality. For instance, the “thali index” — which measures the affordability of two meals per day — shows that 40% of rural and 10% of urban households still cannot afford two thalis a day even after accounting for Public Distribution System (PDS) subsidies. This stark contrast highlights both the importance of the PDS in reducing food deprivation and the urgent need for reform.

What is the Greater Significance of PDS?

The Public Distribution System (PDS) has long been one of the most visible arms of India’s welfare architecture. Its role goes far beyond distributing rice and wheat at subsidised rates.

1. A Tool for Food Security and Welfare

For millions of low-income households, food expenditure takes up a disproportionately large share of income. The PDS, by providing staples at subsidised prices, ensures access to the basic minimum for survival. This has been crucial in preventing hunger and malnutrition, particularly during times of crisis such as droughts, pandemics, or inflationary shocks.

2. A Shield Against Extreme Food Deprivation

Recent data shows that without PDS support, 50% of rural households and 20% of urban households would not be able to afford two thalis a day. PDS reduces this deprivation to 40% and 10% respectively. This demonstrates its role as a buffer against extreme poverty, even if it does not eliminate deprivation entirely.

3. Equalising Staple Food Consumption

Historically, cereal consumption varied significantly between income groups. The PDS has narrowed this gap. Today, the poorest 5% and the richest 5% consume similar levels of cereals. While this does not resolve nutritional gaps, it does reflect universalisation of access to staples, a significant achievement in itself.

4. Instrument of Inclusive Policy

When targeted well, PDS acts as a redistributive tool. By directing subsidies towards the most vulnerable, it helps smoothen inequalities, protect against inflation, and stabilise household consumption. This makes it not just a welfare scheme but a crucial instrument of inclusive economic policy.

What Are the Challenges in Current PDS Practices?

Despite its importance, the current PDS framework suffers from inefficiencies, distortions, and misalignments.

1. Leakage of Subsidies to the Non-Poor

A striking weakness lies in subsidy misallocation. In rural India, households in the 90–95% income bracket receive 88% of the subsidy that the bottom 5% receive. In urban India, nearly 80% of the population continues to receive subsidised cereals, even when they do not need them. This undermines progressivity and wastes resources.

2. Over-Supply of Cereals, Under-Supply of Other Nutrients

Cereal entitlements are excessive. Cereal consumption has already reached saturation across income groups, but nutrient-rich foods like pulses remain out of reach for the poor. For example, pulses consumption among the bottom 5% is half of that among the top 5%. This leads to a situation where calories are universalised but nutrition remains unequal.

3. Inefficient Use of Public Funds

Current policy distributes cereals to 80 crore people (as of January 2024). This is administratively expensive, financially unsustainable, and does not reflect actual consumption needs. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) often struggles with overstocking, wastage, and spiraling storage costs. Public funds that could be directed towards healthcare, education, or nutritional programmes are thus locked into a flawed distribution model.

4. PDS as a “One-Size-Fits-All” System

Uniform entitlements ignore regional contexts and diverse nutritional requirements. For example, in southern India, millets and pulses are more significant in diets than wheat, while in northern states, wheat dominates. By treating all households the same, the system spreads resources too thin without addressing localized food insecurity effectively.

What Reforms Are Needed to Rectify These Challenges?

The PDS must transition from a cereal-centric, quantity-driven system to a nutrition-focused, need-based model.

1. Restructure the Subsidy Regime

Cereal subsidies for upper-income households who already consume more than two thalis/day should be reduced or eliminated. The fiscal savings can be redirected to improve support for the poorest households, ensuring that resources flow where they are most needed.

2. Expand PDS to Include Pulses and Nutrient-Rich Foods

Adding pulses, edible oils, and fortified foods to PDS baskets will address the protein and micronutrient deficits that remain acute among the poorest. For vegetarian households in particular, pulses are a critical protein source.

3. Target Based on the “Thali Index”

Instead of abstract poverty lines, targeting should use direct measures like the Thali Index — the affordability of two balanced meals per day. This would ensure that entitlements reach those in genuine need, aligning welfare with actual food consumption realities.

4. Use NSS 2024 Consumption Data to Calibrate Entitlements

The HCES/NSS 2024 provides granular data on household food patterns. PDS entitlements must be recalibrated accordingly, reducing overstocking burdens on FCI and ensuring better efficiency.

5. Technology-Driven Efficiency

Technology can plug leakages:

-

Aadhaar-seeded ration cards ensure proper identification.

-

One Nation, One Ration Card (ONORC) enables portability across states.

-

Blockchain-enabled supply chains can track grain flow end-to-end, reducing corruption.

-

Smart PDS models using digital food coupons or direct cash transfers (DBTs) can be piloted in urban areas with reliable markets.

Broader Lessons from the Debate on Food Deprivation

The juxtaposition of the World Bank’s 2.3% extreme poverty estimate with the Thali Index’s 40% rural deprivation figure illustrates the multi-dimensional nature of poverty. A household may be above the poverty line yet still unable to afford nutritious food. This underscores the importance of rethinking welfare not just as poverty alleviation but as nutritional security.

Way Forward

-

Shift to Nutrition Security: India must move beyond calories to ensuring balanced diets, particularly in the poorest deciles.

-

Target Smarter, Not Wider: Blanket subsidies dilute impact. Smart targeting using consumption-based indices can achieve more with fewer resources.

-

Strengthen Accountability: Regular audits, social accountability mechanisms, and citizen participation (e.g., community-managed fair price shops) can reduce leakages.

-

Integrate with Health & Education: School midday meals and ICDS can be synergised with PDS to provide a comprehensive nutrition net for children and vulnerable groups.

-

Fiscal Sustainability: A restructured, efficient PDS can free up funds for broader welfare, helping India balance growth with equity.

Conclusion

The Public Distribution System has played a pivotal role in reducing food deprivation in India. By ensuring access to basic cereals, it has narrowed consumption gaps and prevented extreme hunger. Yet, the persistence of nutritional inequality, leakage of subsidies, and inefficiencies show that the PDS cannot remain business-as-usual.

With the release of HCES 2024 and the contrasting findings of the Thali Index, India now has an opportunity to restructure the PDS into a nutrition-sensitive, technology-enabled, and fiscally sustainable model. Doing so will not only protect the poorest from food insecurity but also advance India’s journey towards inclusive and equitable development.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH