Font size:

Print

Legal Aid Systems Need Urgent Revamp to Deliver Justice for All

Legal Aid Systems Hold the Key to Equitable Justice Access

Context: Legal services institutions under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, are mandated to provide free legal aid to nearly 80% of India’s population. Yet, their actual reach remains limited — only 15.5 lakh people accessed legal aid between April 2023 and March 2024, despite a 28% rise from the previous year’s 12.14 lakh.

What are the key challenges faced by legal aid systems in India?

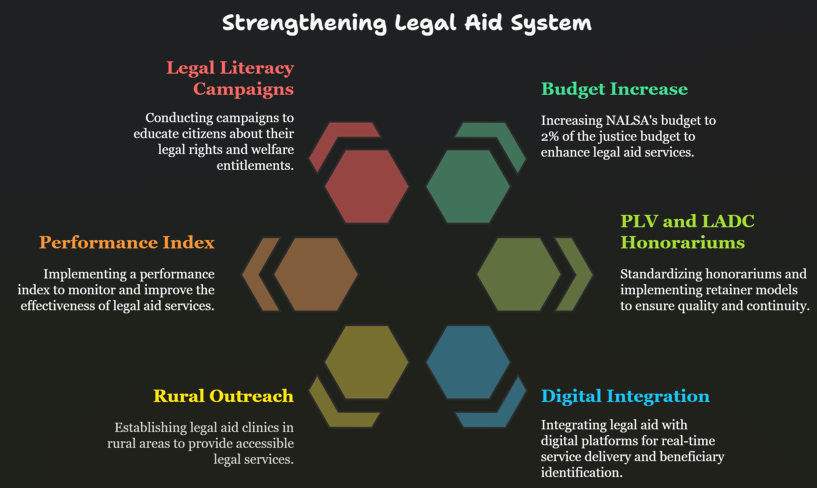

- Low Budget Allocation and Fragmented Funding Structure: Despite being constitutionally mandated (Article 39A), legal aid in India receives less than 1% of the total justice system budget. This underfunding severely constrains infrastructure, human resources, and outreach.

- Skewed Rural Outreach and Institutional Gaps: Legal aid services are disproportionately urban-centric. One legal aid clinic serves, on average, 163 villages, according to the India Justice Report 2025.

- In remote tribal and rural belts, lack of physical access and low legal literacy prevent the marginalised from engaging with the system.

- Declining Para-Legal Volunteer (PLV) Strength: PLVs—often the first point of contact for poor communities—have dropped by 38% between 2019 and 2024.

- Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal had only 1 PLV per lakh population in 2023.

- Bureaucratic Restrictions on Fund Use: NALSA’s 2023 manual restricts expenditure on key services such as hiring project staff, paying for victim compensation, and outreach activities unless specifically approved. These restrictions deter timely responses at the district and village level.

How effective are current legal aid programs in improving access to justice and legal outcomes for the poor?

- Low Beneficiary Reach vs Eligible Population: Though nearly 80% of India’s population is eligible for free legal aid under Section 12 of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, only 15.5 lakh people availed it in 2023–24—an improvement from the previous year, but still far below the required scale.

- Emerging Potential of Legal Aid Defence Counsel (LADC): To professionalise representation for accused persons, NALSA launched the Legal Aid Defence Counsel Scheme (LADC) in 2022, now active in 610 out of 670 districts.

- State Disparities in Legal Aid Spending: According to the Economic Survey 2023–24 and actual spending figures from NALSA, per capita spending varies drastically: Haryana: ₹16, Jharkhand & Assam: ₹5, Uttar Pradesh: ₹4, Bihar: ₹3, West Bengal: ₹2. This creates uneven justice delivery across States.

- Positive but Limited Lok Adalat Impact: While Lok Adalats and mediation centres promote quick disposal of cases, most are limited to compoundable offences and civil matters. They have succeeded in reducing pendency (as per NALSA Annual Report 2023) but are not substitutes for substantive legal redress for serious rights violations.

What are the main shortcomings in the implementation and resource allocation for legal aid initiatives, and how do these affect their impact?

- Unrevised Honorariums and Delayed Disbursements: PLVs are paid per day, with many States failing to revise honorariums despite inflation. For instance, as of March 2023: Kerala: ₹750/day, 22 States: ₹500/day & Gujarat, Meghalaya, Mizoram: ₹250/day. This demotivates the frontline workforce and leads to high attrition.

- Limited Flexibility in District Legal Services Authorities (DLSAs): DLSAs cannot independently hire staff, conduct outreach, or deploy mobile legal clinics due to strict fund-utilisation clauses under the NALSA Manual (2023).

- Absence of Accountability and Feedback Mechanisms: There is no standardised grievance redressal or audit system for legal aid quality across districts. Beneficiaries often face dismissive attitudes, poor representation, or delays. The Justice Clock initiative for digitised justice delivery does not include feedback on legal aid efficacy.

- Underutilisation of Social Action Litigation (SAL): Though NALSA is empowered to file social action litigation for vulnerable groups, few cases are proactively initiated. This undercuts the potential of legal aid to address structural issues like bonded labour, caste discrimination, or land alienation in tribal areas.