Left Wing Extremism Used as Pretext: Maharashtra’s Controversial Law Sparks Alarm

Left Wing Extremism Label Weaponised: New Law Threatens Civil Liberties in Maharashtra

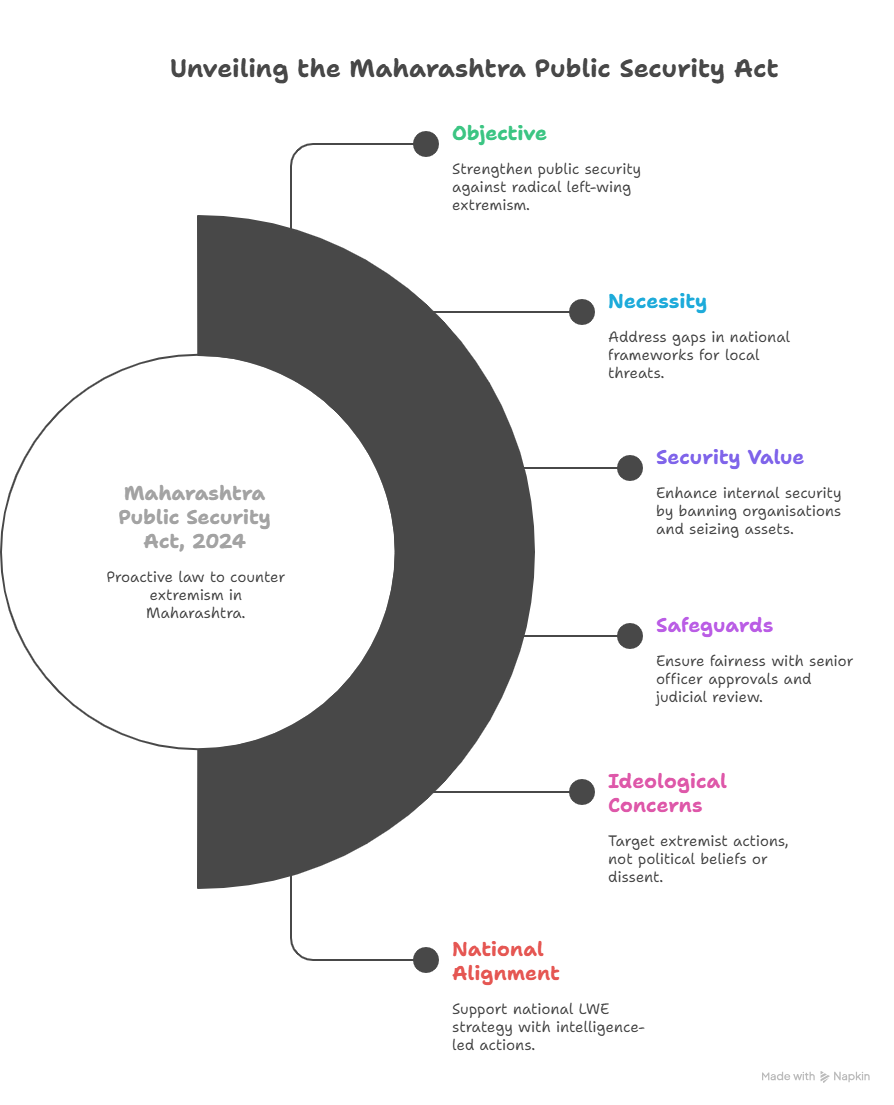

Context: The Maharashtra Assembly passed the Maharashtra Special Public Security Act, 2024 aimed at curbing extremist threats to constitutional institutions and national integrity.

Where does this law fit in India’s legal and constitutional framework?

The Act overlaps with and possibly violates multiple provisions of the Indian Constitution, especially:

- Article 19(1)(a): Freedom of speech and expression

- Article 19(1)(b): Right to peaceful assembly

- Article 21: Right to life and personal liberty

Though Article 19(2) allows “reasonable restrictions”, the Act’s language—like “disturbing tranquility” or “preaching disobedience”—fails the test of legal clarity and reasonableness mandated by Supreme Court verdicts like Shreya Singhal vs. Union of India (2015).

What is the Maharashtra Special Public Security (MSPS) Act, 2024?

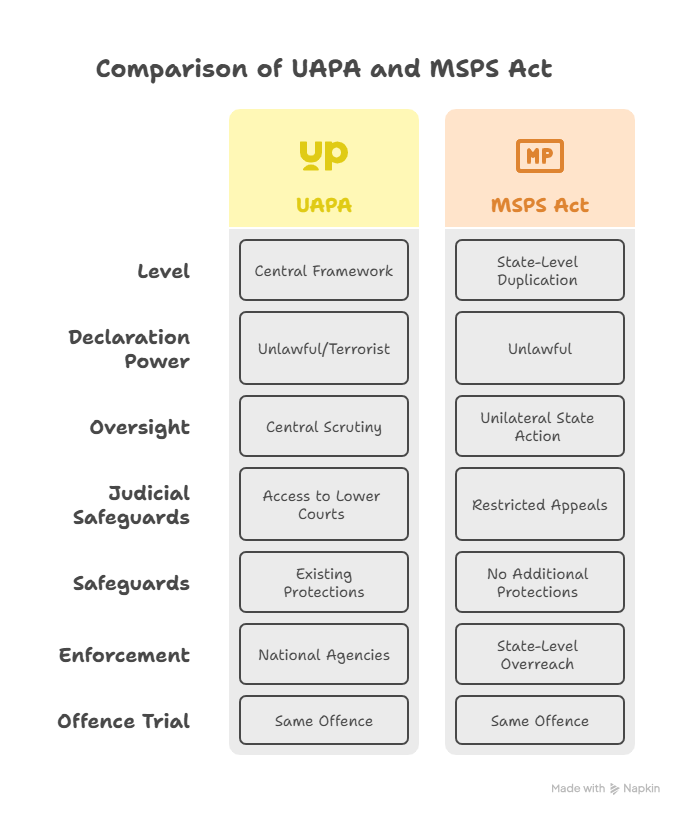

It allows the government to declare any organisation or individual as “unlawful” based on alleged links to Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) or activities that pose a threat to public order, peace, and constitutional institutions.

Key Provisions:

- Declares individuals/groups as “unlawful” via executive notification.

- Covers not just violent acts but also speech, writings, gestures that cause “fear” or “encourage disobedience”.

- Enables property seizure, bans, and arrests based on suspicion.

- Offences are non-bailable and cognizable.

- Investigation only by officers above DSP rank; cases initiated only with DIG+ level approval.

- Judicial review limited to High Courts and the Supreme Court.

Why has the law been introduced now?

- The law has been presented as a pre-emptive response to ‘urban Naxalism’, a term often used to describe alleged Maoist sympathisers in academic or activist spaces. Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis claims the law aims to protect constitutional integrity from “radical left-wing ideology”.

- Contextual Timing: Comes at a time when the Union government claims that LWE is at its lowest ebb.

-

- Coincides with rising criticism of the government’s handling of dissent.

- Follows precedents in Telangana, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Jharkhand, where similar laws exist.

Who can be affected by the law?

- Under the law’s broad and ambiguous definitions, virtually any individual or group involved in public protests, civil society work, or academic discourse can be Labelled as unlawful & Investigated, detained, or punished, even without committing violent acts.

- Vulnerable Groups:

-

- Social workers and civil rights activists

-

- Academic institutions holding seminars

-

- Student unions or informal discussion groups

-

- Journalists and documentary filmmakers

- Example: A Shiv Sena leader recently alleged that “urban Naxals” participated in the Ashadi Wari pilgrimage, showing how loosely the term is used.

What are the major criticisms of the law?

- Vague and Overbroad Definitions: Terms like “unlawful activity”, “frontal organisation”, “fear or apprehension”, and “disobedience” are undefined. This leads to legal uncertainty and arbitrary interpretation by the executive.

- Ideological Criminalisation: The law shifts focus from punishing acts to targeting beliefs and associations which poses a danger to academic freedom, dissenting political thought, and civil liberties.

- Disproportionate Powers: Allows arrests without warrant, no bail, and limited judicial oversight ,Gives immunity to officials acting “in good faith”, enabling potential misuse. Case Reference: The death of Father Stan Swamy, an 84-year-old activist jailed under the UAPA without trial, highlights the dangers of vague anti-extremism laws.

What about safeguards and checks?

- While the law claims to involve an Advisory Board of retired High Court judges for review, it

- Comes into play after arrests or bans

- Has no requirement for public hearings or transparency

- Is not a judicial body with enforceable powers

- Thus, the “check” is symbolic, not substantive.