Indus Valley Civilisation: Key Facts for UPSC

Complete UPSC guide on Indus Valley Civilisation – major sites, chronology, town planning, economy, culture, religion, script, and decline.

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) is a crucial topic for UPSC preparation due to its historical, archaeological, and cultural significance. As one of the world’s earliest urban civilisations, it lays the foundation for understanding ancient Indian history. The topic is frequently covered in both Prelims (questions on sites, artefacts, and features) and Mains (topics like urban planning, social structure, and theories of decline). It also connects with art, culture, geography, and current affairs, especially through recent archaeological discoveries like Rakhigarhi. Studying IVC helps aspirants develop a comprehensive understanding of early Indian society, making it a high-yield and multidisciplinary area essential for scoring well in the exam.

The Harappan Civilisation: India’s First Urban Culture

Discovery and Nomenclature

The earliest excavations associated with the Indus Valley were conducted at Harappa in West Punjab and Mohenjodaro in Sindh, both of which are now located in Pakistan. These monumental discoveries unearthed a sophisticated civilisation, initially termed the Indus Valley Civilisation owing to its location. However, as further sites were discovered far beyond the Indus region—including in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab—the term Harappan Civilisation became more appropriate. It was so named because Harappa was the first site excavated, marking the beginning of systematic archaeological investigation into this Bronze Age civilisation.

Major Harappan Sites

Geographical Spread

- The Harappan civilisation covered a vast area, extending across:

- India: Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and western Uttar Pradesh.

- Pakistan and parts of Afghanistan.

Notable sites among them are:

- Harappa (Punjab, Pakistan)

- Mohenjodaro (Sindh, Pakistan)

- Kalibangan (Rajasthan, India)

- Rupar (Ropar) (Punjab, India)

- Banawali (Haryana, India)

- Rakhigarhi (Haryana, India)

- Lothal, Dholavira, and Surkotada (Gujarat, India)

- Chanhudaro (Sindh, Pakistan)

- Daimabad (Maharashtra)

- Kot Diji (Sindh, Pakistan)

- Manda (Jammu & Kashmir)

- Shortughai (Afghanistan)

- Sutkagendor (near Pakistan-Iran border)—the westernmost site

- Alamgirpur (Uttar Pradesh)—easternmost site

The largest among these was Mohenjodaro, spread over nearly 200 hectares, followed by Harappa and Dholavira.

Chronology of the Harappan Culture

Determining the exact dates of the Harappan Civilisation has evolved over time. Initially, in 1931, Sir John Marshall estimated its timeline as 3250–2750 BCE. With the advent of radiocarbon dating, more accurate timelines were established. Notable scholars like Fairservis and D.P. Agarwal later proposed that the civilisation spanned from 2300 BCE to 1750 BCE. Today, most historians agree on the following chronological phases:

- Pre-Harappan Phase (c. 7000–2600 BCE)

- Early Harappan Phase (c. 2600–2500 BCE)

- Mature Harappan Phase (c. 2500–1900 BCE)

- Late Harappan Phase (c. 1900–1300 BCE)

Salient Features of the Harappan Culture

Town Planning

- Harappan cities were known for systematic town planning, especially the grid pattern—streets intersecting at right angles.

- Two-part city structure:

- Citadel (Acropolis): Possibly housed the ruling class.

- Lower town: Inhabited by common people, had brick houses.

- Mohenjo-daro had more advanced structures than Harappa.

- Town planning and large buildings indicate:

- Efficient tax collection.

- Capability to mobilise labour.

- Use of architecture to showcase authority.

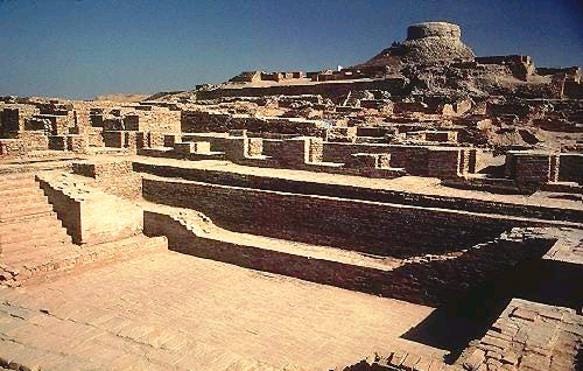

- Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro:

- Located on the citadel mound.

- Size: 11.88 × 7.01 m, depth 2.43 m.

- Brick floor, with steps, changing rooms, and drainage.

- Water from adjacent large well, used for ritual bathing.

- Comparable to a large tank at Dholavira.

- Mohenjo-daro: Largest building was a granary (45.71 × 15.23 m).

- Harappa:

- Had six granaries, arranged in two rows.

- Each granary: 15.23 × 6.09 m; total space ≈ 838 sq. m.

- Located near the river.

- Nearby were circular brick platforms, likely used for threshing grain (grains found in crevices).

- Two-roomed barracks possibly housed laborers.

- Kalibangan: Also had brick platforms, likely used for storing grain.

- Shows that granaries were central to Harappan urban planning.

- Burnt bricks widely used across Harappan cities.

- Superior to Egyptian (which used sun-dried bricks) and Mesopotamian practices (less extensive use of baked bricks)

- Highly advanced drainage system, especially in Mohenjo-daro.

- Almost all houses had:

- Courtyards and bathrooms.

- Individual wells (notably in Kalibangan).

- Drains connected to street drains, often covered with bricks or stone slabs.

- Remains of streets and drains are also

- 3. found at Banawali.

- Emphasis on health and cleanliness was unmatched in other Bronze Age civilizations.

Agriculture

- Though the Indus region receives only about 15 cm of rainfall today, it was much more fertile in ancient times.

- A historian from Alexander’s time (4th century BCE) described Sindh as a fertile part of India.

- Earlier, dense natural vegetation in the region helped maintain rainfall and provided timber for brick-making and construction.

- Over time, vegetation was depleted due to expanding agriculture, overgrazing, and demand for fuel.

- The main source of fertility was the annual flooding of the Indus River, which brought nutrient-rich silt.

- The presence of brick flood-protection walls indicates that floods occurred every year.

- Just as the Nile nurtured Egypt, the Indus sustained Sindh.

- Crops were sown in November on flood plains and harvested by April, before the next floods.

- Though no iron tools have been found, furrow marks at Kalibangan suggest fields were ploughed.

- Farmers likely used wooden ploughs drawn by oxen; camels may have also been used.

- Stone sickles were probably used to harvest crops.

- Canal irrigation was likely not practiced.

- In regions like Baluchistan and Afghanistan, water was stored using gabarbands or dams built across seasonal streams.

- Most Harappan villages were near flood plains, ensuring water availability for farming.

- Key crops included wheat, barley, peas, mustard (rai), and sesame (til).

- Two varieties of wheat and barley were cultivated.

- Banawali yielded significant amounts of barley.

- Rice was cultivated at Lothal as early as 1800 BCE.

- Large granaries were built at Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and possibly Kalibangan to store food grains.

- Grains may have been collected as taxes from farmers.

- Stored grain was used to:

- Pay workers and officials

- Provide for emergencies

- This system was similar to that of Mesopotamian cities, where workers were paid in barley.

- The Indus people were the first to cultivate cotton.

- The Greek term “Sindon” (meaning cotton) was derived from the word Sindh.

Domestication of Animals

- Harappans practised both agriculture and large-scale animal rearing.

- Domesticated animals: oxen, buffaloes, goats, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats, donkeys, camels.

- Humped bulls were especially preferred.

- Horses: doubtful evidence; not central to Harappan culture.

- Elephants were domesticated; rhinoceroses were known.

- Unlike Mesopotamians, Harappans in Gujarat grew rice and domesticated elephants.

Technology and Crafts

-

- The rise of towns in the Indus Valley was based on:

- Agricultural surplus

- Bronze tool production

- Development of various crafts

- Widespread trade and commerce

- This marked the first urbanisation in India during the Bronze Age.

- Harappans used both stone and bronze tools.

- Bronze was typically made by mixing tin with copper, occasionally arsenic with copper.

- Due to the limited availability of tin and copper, bronze tools were not common.

- Sources of metals:

Copper: Khetri mines (Rajasthan) and Baluchistan

Tin: Likely from Afghanistan, and possibly from Hazaribagh and Bastar in India

- Harappan bronze tools contained low amounts of tin.

- Numerous bronze-working kits indicate that bronze smiths were a key artisan group.

- Bronze items included:

Images and utensils

Tools like axes, saws, knives, and spears

Other important crafts in Harappan towns:

- Textile production:

-

-

- Woven cotton found at Mohenjo-daro

- Textile impressions found on objects

- Use of spindle whorls for spinning

- Production of wool and cotton fabrics

- Bricklaying was significant, as seen in large brick structures

-

- Boat-making was practiced

- Seal-making and terracotta production were prominent

- Jewellery-making:

-

-

- Used gold, silver, and precious stones

- Gold and silver possibly from Afghanistan

- Precious stones from South India

-

- Bead-making was highly developed

- Pottery:

- Widespread use of the potter’s wheel

- Known for glossy, gleaming pottery

Trade and Commerce

- The importance of trade in Indus society is evident from the presence of granaries at Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Lothal.

- Numerous seals, a standardised script, and uniform weights and measures found over a vast area further emphasise the organised nature of their trade.

- The Harappans were actively engaged in trading stone, metal, shells, and other goods within their cultural zone.

- Since their cities lacked essential raw materials, they relied on imports for production.

- Barter was the likely method of exchange, as there is no sign of coin-based currency.

- Trade was facilitated through boats along the Arabian Sea and bullock-carts on land.

- The Harappans had knowledge of the wheel, using carts with solid wheels, similar to early ekkas (but without spokes).

- The Indus people maintained trade ties with Rajasthan, Afghanistan, and Iran.

- A trading settlement in northern Afghanistan helped connect with Central Asia

- They had commercial exchanges with the Tigris-Euphrates civilisations.

- Discovery of Harappan seals in Mesopotamia confirms direct contact.

- Some cosmetic practices of Mesopotamia were possibly adopted by the Harappans.

- Lapis lazuli was an important long-distance trade item, likely associated with elite status.

- Mesopotamian records from around 2350 BCE mention trade with Meluha, an ancient name for the Indus region.

- Dilmun (probably Bahrain) and Makan were key intermediary trading hubs between Mesopotamia and Meluha.

- The port city of Dilmun has thousands of unexcavated graves, suggesting a significant trade center.

Social Organisation

- Excavations reveal a social hierarchy in Harappan urban settlements.

- Cities like Harappa, Kalibangan, and Dholavira were divided into three distinct zones.

- The citadel area likely housed the elite or ruling class.

- The lowest part of the city was meant for the common populace.

- The middle zone may have accommodated officials and middle-class traders.

- It is still unclear if this division was based on occupation or socioeconomic status.

- Variations in residential structures indicate social differences—houses ranged from one to twelve rooms.

- In Harappa, two-room houses were probably used by artisans and labourers.

- This pattern suggests a stratified society within the same urban space.

Polity

- The widespread uniformity of Harappan culture suggests the presence of a centralised authority.

- Based on Kautilya’s Arthashastra, essential components of a state—such as sovereignty, ministers, population, forts, treasury, military force, and allies—can be identified in the Harappan system.

- The citadel likely served as the seat of power, while the middle town may have been home to bureaucrats or administrative offices.

- The great granary at Mohenjo-daro possibly acted as the state treasury, with taxes collected in the form of grain.

- The Indus region was densely populated, and many cities, like Dholavira, featured strong fortifications, including forts within forts.

- Although there is no firm evidence of a standing army, findings such as a heap of sling stones and a soldier depiction on a potsherd at Surkotada hint at a possible organised force.

- By the mature phase, the Harappan state was well developed and structured.

- Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, no temples or religious buildings have been found in Harappan cities, except for the Great Bath, possibly used for ritual cleansing—indicating that priests did not rule.

- The Harappan rulers were more engaged in trade and commerce than in military expansion.

- The ruling class may have been merchants, and the limited discovery of weapons suggests the absence of a strong warrior class.

Religious Practices

- Numerous terracotta figurines of women have been found at Harappa.

- One figurine depicts a plant growing from a woman’s womb, possibly symbolising the earth goddess.

- This suggests the Harappans worshipped the earth as a fertility goddess, similar to how Egyptians worshipped the Nile goddess Isis.

- It is uncertain whether Harappan society was matriarchal like Egypt, where daughters inherited property or the throne.

- Some Vedic texts show reverence for the earth goddess but do not emphasise her worship.

- Widespread worship of the supreme goddess in Hinduism developed much later, around the 6th century AD.

- From then, mother goddesses like Durga, Amba, Kali, and Chandi became prominent in Puranic and tantric texts.

- Eventually, every village came to have its own local goddess.

The Male Deity in the Indus Valley

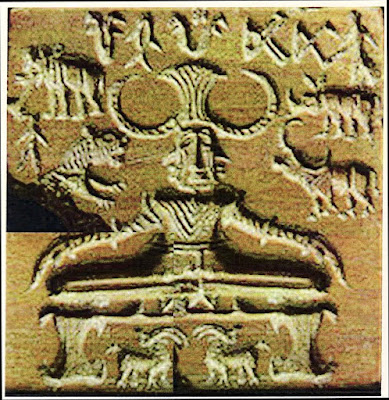

- A male deity appears on a Harappan seal with three horned heads, seated in a yogic posture (one leg over the other).

- The deity is surrounded by an elephant, tiger, rhinoceros, with a buffalo beneath the throne, and two deer near his feet.

- He is often identified as Pashupati Mahadeva (an early form of Shiva), but this link is uncertain, as the bull is absent, and similar horned deities are found in other ancient cultures

- There is evidence of phallic worship in Harappa, with many stone representations of male and female sex organs, likely used for ritual purposes.

- The Rig Veda mentions non-Aryan communities who practiced phallic worship.

- This form of worship, which began in the Harappan period, was later absorbed into mainstream Hinduism, particularly in the worship of Shiva.

Tree and Animal Worship

- The Harappans worshipped trees, especially the pipal tree, as shown on a seal depicting a deity amidst its branches.

- The pipal tree remains sacred in India even today.

- Animal worship was common, with many animals depicted on seals:

The most significant is a unicorn-like animal, possibly representing a rhinoceros. The humped bull also held religious importance and is still revered in Hindu culture.Animals shown around the ‘Pashupati Mahadeva’ figure (such as elephant, tiger, etc.) suggest these were also worshipped. - The Harappans worshipped deities in the form of trees, animals, and human-like figures.

- Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, they did not build temples for their gods.

- The Harappan script remains undeciphered, so their religious beliefs cannot be fully understood.

- Numerous amulets have been found, likely used to protect against evil forces and spirits.

- This practice is similar to the beliefs in the Atharva Veda, which includes charms, spells, and protective rituals from non-Aryan traditions.

The Harappan Script

- The Harappans developed their own system of writing, much like the ancient Mesopotamians.

- The first example of the Harappan script was discovered in 1853, and a more complete form came to light by 1923.

- The script remains undeciphered, so we cannot assess their literary contributions or understand their beliefs and ideas.

- Scholars have attempted to relate the script to Dravidian, proto-Dravidian, Sanskrit, and Sumerian languages, but none of these interpretations are satisfactory.

- Around 4000 examples of Harappan writing have been found, mainly on stone seals and various objects.

- In contrast to Egyptian and Mesopotamian traditions, Harappans did not produce lengthy inscriptions.

- Most inscriptions are brief, possibly used to mark ownership or property.

- The script includes roughly 250 to 400 pictographic signs.

- It is largely pictographic, where each symbol likely represents a sound, object, or idea.

- Although comparisons have been made with Mesopotamian and Egyptian scripts, the Harappan script is considered a unique and indigenous creation of the Indus Valley civilisation.

Weights and Measures

-

The Harappans knew the art of writing, which likely helped in recording private property and maintaining accounts.

-

Weights and measures were essential for trade and transactions in urban Indus society.

-

Many weight artifacts have been discovered; they mainly follow a system based on 16 and its multiples (e.g., 16, 64, 160, 320, 640).

-

The base-16 tradition persisted in India—16 annas made a rupee until recently.

-

Harappans also developed measurement tools, including marked measuring sticks, one of which was made of bronze

Harappan Pottery

Seals

-

The Harappans were highly skilled in using the potter’s wheel.

-

Excavated pottery is predominantly red and includes forms such as the dish-on-stand.

-

Many vessels feature painted decorations with diverse patterns.

-

Typical designs include tree motifs, circular patterns, and occasionally human figures.

Images

- Harappan artisans excelled in metal and stone sculpture.

- The finest example is a bronze figurine of a female dancer, depicted nude except for a necklace.

- A few stone sculptures have also been unearthed.

- One steatite statue is shown wearing a decorated robe draped over the left shoulder and under the right arm, resembling a shawl.

- The figure’s short hair at the back is secured with a woven headband.

Terracotta Figurines

- Numerous figurines were made from fire-baked clay, known as terracotta.

- These were used either as toys or for religious worship.

- They depict animals such as birds, dogs, sheep, cattle, and monkeys.

- Human figures are also common, with more female than male representations.

- Seals and images exhibit refined and skilled craftsmanship.

- Terracotta objects are simpler and less artistically developed.

- The contrast in quality suggests a class divide: Seals and images were likely used by the upper class and Terracotta items were used by the common people.

Stone Work

- Harappa and Mohenjodaro show little stone work due to a lack of local stone resources.

- Dholavira, located in Kutch, had access to stone and shows extensive use of it.

- The citadel of Dholavira is built of stone and is the most impressive among Harappan citadels.

- Dressed stone was used in masonry along with mud bricks, which is considered remarkable.

- Stone slabs were used in three types of burials at Dholavira.

- One burial type features a circle of stones above the grave, resembling a megalithic stone circle.

The exact cause of the decline of Harappan culture is still uncertain and widely debated.

Decline of the Harappan Culture

Scholars have proposed several natural factors as possible reasons:

- Frequent floods

- Drying up of important rivers

- Decline in soil fertility due to overuse

- Earthquakes disrupting settlements

Another theory suggests the Aryan invasion as a major cause:

- The Rig Veda mentions the destruction of forts, possibly referring to Harappan cities

- Human skeletons found in clustered positions at Mohenjodaro hint at a sudden, violent end.

- The Aryans’ use of superior weapons and fast horses may have given them a military advantage.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH