India’s Urban Definition Fails Growing Towns

India risks misclassifying growing towns under outdated Census rules. Learn why redefining “urban” is vital for governance, infrastructure, and equity.

Context

The Registrar General of India has proposed retaining the 2011 Census definition of urban areas for Census 2027. This decision has sparked concerns that rapidly urbanising settlements may continue to be misclassified as rural, depriving them of adequate governance, infrastructure, and resources. As India undergoes one of the fastest urban transitions globally, the stakes of how “urban” is defined are significant for both governance and development.

Major Limitations of the 2011 Census Definition of ‘Urban’

The 2011 Census of India classified urban areas into two categories:

-

Statutory Towns – Settlements officially notified by state governments with urban local bodies (ULBs) such as municipalities, corporations, or cantonment boards.

-

Census Towns – Rural settlements that met three criteria:

-

Minimum population of 5,000.

-

At least 75% of the male working population engaged in non-agricultural activities.

-

Population density of at least 400 persons per square kilometre.

-

While straightforward, this definition has critical shortcomings.

1. Gender Bias

The criterion of 75% male workforce in non-agricultural activities ignores women’s economic roles, particularly in informal, unpaid, and home-based labour. Women’s contribution in peri-urban and transitioning areas is systematically undercounted, leading to skewed classifications.

2. Exclusion of Informal Employment

India’s urbanisation today is shaped not just by formal industry but also by the informal sector and the gig economy. Migrants, construction workers, service providers, and app-based gig workers often operate in settlements classified as rural, even though these areas function as de facto urban clusters.

3. Narrow Thresholds

The rigid cut-offs for population size, density, and occupational structure fail to capture settlements that exhibit urban characteristics but miss one or two benchmarks. This leaves many semi-urban and peri-urban areas outside the official definition of “urban.”

Implications on Governance

The outdated classification has far-reaching effects on governance, planning, and resource allocation.

1. Delayed Urbanisation Recognition

The misclassification of settlements slows recognition of urban growth. For instance, in West Bengal, 251 settlements that were census towns in 2001 continued to remain under rural governance by 2011. These delays prevent the timely extension of urban governance frameworks.

2. Inadequate Infrastructure and Services

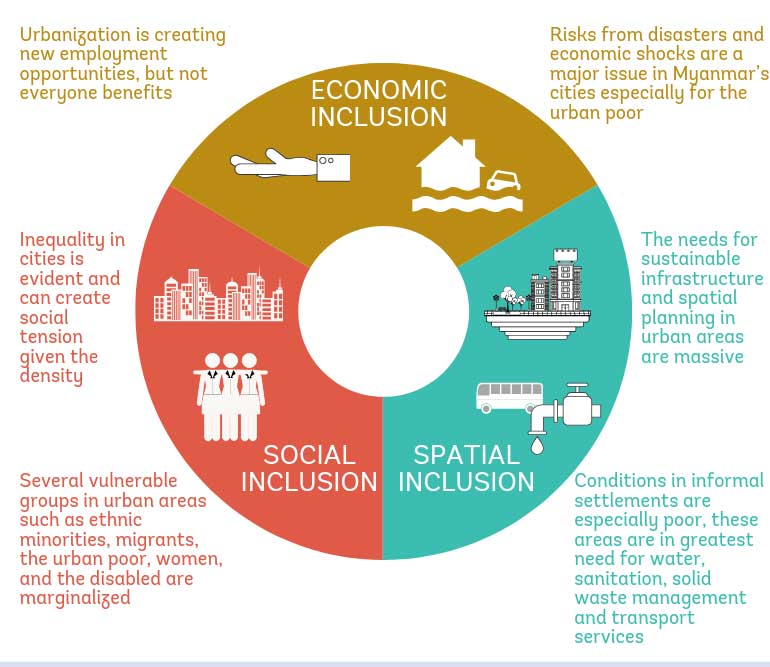

Areas that function like towns but are labelled “rural” often lack urban planning, sanitation, healthcare, and transport systems. Without urban local bodies, they depend on Panchayati Raj institutions that are typically designed for rural welfare schemes, not urban service delivery.

3. Exclusion from Urban Benefits

Such settlements are denied access to urban development schemes, fiscal transfers, and institutional autonomy. This exclusion stifles their economic potential, creating mismatches between actual needs and available resources.

Why Updating the Urban Definition Matters

India’s urbanisation is no longer confined to metropolitan cities. Small and medium towns, peri-urban belts, and clustered villages are driving much of the growth. Failing to classify them correctly risks creating:

-

Service delivery deficits, with housing, water, and waste management lagging behind.

-

Economic bottlenecks, as emerging hubs lack financial support for infrastructure.

-

Social inequalities, since residents of urban-like settlements are denied access to schemes available in cities.

Without timely recognition, these areas fall into a governance vacuum, neither rural enough for Panchayat models nor urban enough for municipal planning.

Recommendations for Redefining ‘Urban’

To ensure that India’s urbanisation process is both inclusive and effective, several reforms are needed:

1. Inclusive Criteria

Introduce gender-sensitive indicators that account for women’s informal and unpaid work. Recognising informal employment and gig economy participation will also provide a more accurate reflection of settlement realities.

2. Functional and Dynamic Classification

Move beyond rigid thresholds to a functional approach—classifying areas based on actual characteristics such as commuting patterns, built-up areas, and economic activity. A dynamic classification would allow settlements to transition more smoothly between rural and urban categories.

3. Regular Updates

Rather than waiting a decade between censuses, classification should be periodically reviewed to reflect rapid socio-economic and demographic changes. Mid-decade reviews, AI-based spatial analysis, and satellite imagery can support this.

Conclusion

The proposal to retain the 2011 Census definition of “urban” risks perpetuating governance blind spots for India’s fast-growing settlements. With more than 65% of India’s future urban growth expected in smaller towns and peri-urban belts, redefining “urban” is urgent. A forward-looking, inclusive, and flexible classification system would not only ensure equitable resource allocation but also strengthen India’s capacity to manage its urban transition sustainably.

India’s urban future depends not only on infrastructure and investment but also on how accurately it recognises and governs its changing settlement patterns. Updating the definition of “urban” is therefore not a technical detail—it is a foundational step in shaping India’s growth trajectory.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH