India’s Poverty Reduction

Analysing poverty levels in India

Context: A recent research paper titled “Poverty Decline in India after 2011–12: Bigger Picture Evidence” reveals that the pace of poverty reduction in India has significantly slowed since 2011–12.

More on News

- Authored by economists Himanshu (Jawaharlal Nehru University), Peter Lanjouw, and Philipp Schirmer (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), the study provides a comprehensive analysis in the absence of official poverty data from the Indian government post-2011–12.

Key Findings: Poverty Reduction Has Lost Momentum

- Marginal Decline: The paper highlights that poverty in India, which fell from 37% in 2004–05 to 22% in 2011–12, has declined only marginally since then — reaching an estimated 18% in 2022–23.

- This implies that while 250 million people were poor in 2011–12, the number dropped only slightly to around 225 million by 2022–23.

Lack of Official Data and Methodological Challenges

Since India hasn’t published official poverty statistics after 2011–12, researchers have turned to alternative methods and datasets to estimate poverty. The study groups these into three primary methodological approaches:

- Use of NSSO Surveys: Many estimates rely on socio-economic surveys from the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), particularly the Usual Monthly Per Capita Consumption Expenditure (UMPCE).

- However, since UMPCE is based on a single ambiguous question, the data lacks comparability with earlier consumption surveys.

- Estimates from this method suggest poverty was between 26% and 30% in 2019–20.

- National Accounts Approach: A 2022 study by economist Surjit Bhalla and colleagues used the Private Final Consumption Expenditure (PFCE) from National Accounts Statistics to extrapolate consumption trends.

- This method scaled 2011–12 data using the growth rate of PFCE, offering another estimate but with limitations in accuracy.

- Survey-to-Survey Imputation: The authors of the current study use this method — also employed in World Bank research — to bridge data gaps between different surveys.

- They specifically used employment surveys, like the Employment-Unemployment Survey (EUS) and Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), which are methodologically aligned with the 2011–12 Consumption Expenditure Survey.

What Makes This Study Different?

The authors highlight three unique aspects of their methodology:

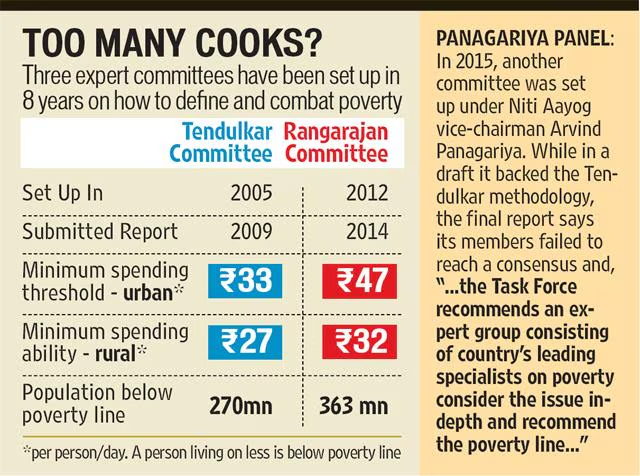

- Tendulkar Poverty Line: Unlike studies that use World Bank poverty thresholds, this study adheres to India’s official Tendulkar Committee poverty line.

- Methodological Consistency: The use of NSSO’s employment surveys ensures methodological consistency, enhancing the reliability of imputed consumption data.

- State-Level Estimates: By estimating poverty at the state level or using state-fixed effects, the authors present a more granular and accurate poverty map.

State-Wise Poverty Trends Show Divergence

- While Uttar Pradesh made notable strides in poverty reduction, states like Bihar and Jharkhand lagged behind.

- In fact, several large states such as Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh witnessed stagnation in poverty alleviation.

Slower Economic Growth and Rising Informality Are Key Factors

The paper links the slowdown in poverty reduction to broader economic trends:

- Lower GDP Growth: India’s GDP growth fell from an annual average of 6.9% (2004–05 to 2011–12) to just 5.7% in the following decade.

- Wage Stagnation: Rural wage growth halved from 4.13% per year (2004–2012) to just 2.3% (2012–2023), affecting household consumption.

- Return to Agriculture: After years of declining agricultural employment, 68 million workers re-entered the sector since 2017–18, reflecting distress and reversing gains in labor productivity.

Need for New Official Data and Renewed Policy Focus

- Despite its robust methodology, the study emphasises that a comprehensive understanding of poverty trends in India is not possible without updated official consumption data.

- Still, the convergence of multiple data points — from GDP trends to wage growth and labour shifts — strongly suggests that poverty reduction has stagnated.

This study may not settle the debate on poverty in India, but it sends a clear signal: the momentum gained between 2004 and 2012 has weakened, and targeted policy interventions are urgently needed. With rising economic inequality and rural distress, India must accelerate efforts to lift millions out of poverty — especially in states and sectors that are being left behind.