Font size:

Print

Health Governance Challenges in Rural and Slum Areas: Anganwadis as a Powerful Tool for Child Nutrition

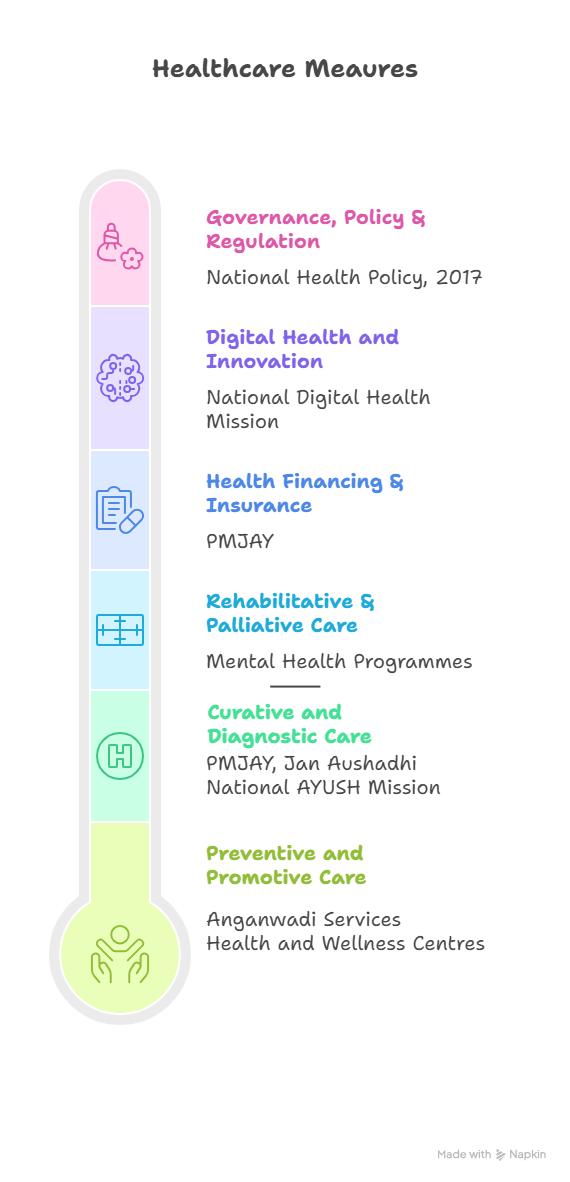

Context: The ongoing crisis in Maharashtra’s Anganwadis over poor-quality nutrition and worker protests highlights how gaps in ICDS delivery threaten food security, child health, and women’s welfare in present times.

What is the health status of rural and slum dwellings in India?

Health indicators for rural and slum populations reveal persistent gaps compared to urban areas.

- NFHS-5 (2019–21) shows Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) at 34 per 1,000 live births in rural areas versus 23 in urban; under-5 mortality stands at 41 in rural and 31 in urban.

- Urban slums mirror rural health outcomes despite geographical proximity to health facilities. According to the National Sample Survey (75th Round, 2017–18), only 18% of slum households had access to piped drinking water compared to 40% of non-slum urban households.

- Economic Survey 2022–23 highlighted that ¬50% of underweight children are concentrated in rural and slum settlements, with stunting highest in states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra’s tribal belts.

What are the prominent health challenges in these areas?

- Malnutrition: Rural and slum children disproportionately suffer from stunting and wasting; NFHS-5 reported 35% stunting nationally, highest in marginalised districts.

- Maternal health risks: Higher prevalence of anaemia (57% in rural women vs 50% urban).

- Communicable diseases: Poor sanitation and overcrowding in slums accelerate TB, diarrhoea, and vector-borne diseases.

- Non-communicable diseases (NCDs): Rising hypertension and diabetes remain underdiagnosed due to limited screening.

- Infrastructure gap: Rural health centres face a 25% shortfall in doctors at PHCs (Rural Health Statistics 2022).

What are the challenges faced by Anganwadis in health governance?

- Quality of nutrition: As seen in Maharashtra, premixed khichdi and protein powders under ICDS are often rejected by children and mothers due to poor taste and contamination.

- Low budget allocation: Supplementary nutrition cost remains ₹8 per child/day, unchanged since 2014.

- Work pressure: Workers manage preschool, nutrition, surveys, and health outreach with minimal wages (₹10,500/month for sevika).

- Technological hurdles: Mandated Aadhaar-linked facial recognition (Take Home Ration (THR) through the Poshan Tracker App) has led to exclusion errors.

- Lack of social security: No provident fund or pension, leading to strikes and livelihood insecurity .

Case Study: Tamil Nadu’s Amma Unavagam model and decentralised kitchen-based ICDS have achieved higher child nutrition outcomes compared to centralised contractors (Down to Earth, 2022).

How can Anganwadis be made more effective?Enhance funding: Economic Survey recommends raising nutrition expenditure; per child outlay must be inflation-indexed.

- Community participation: Successful states like Tamil Nadu run hot cooked meal models instead of centralised premix.

- Capacity building: Digital training, reduced paperwork, and adequate infrastructure (weighing scales, registers).

- Worker welfare: Regularise employment status, provide social security (pension, health insurance).

- Monitoring and quality assurance: Local SHGs and Panchayati Raj institutions should oversee ration quality and delivery.