Font size:

Print

Criminalisation of Indian Politics

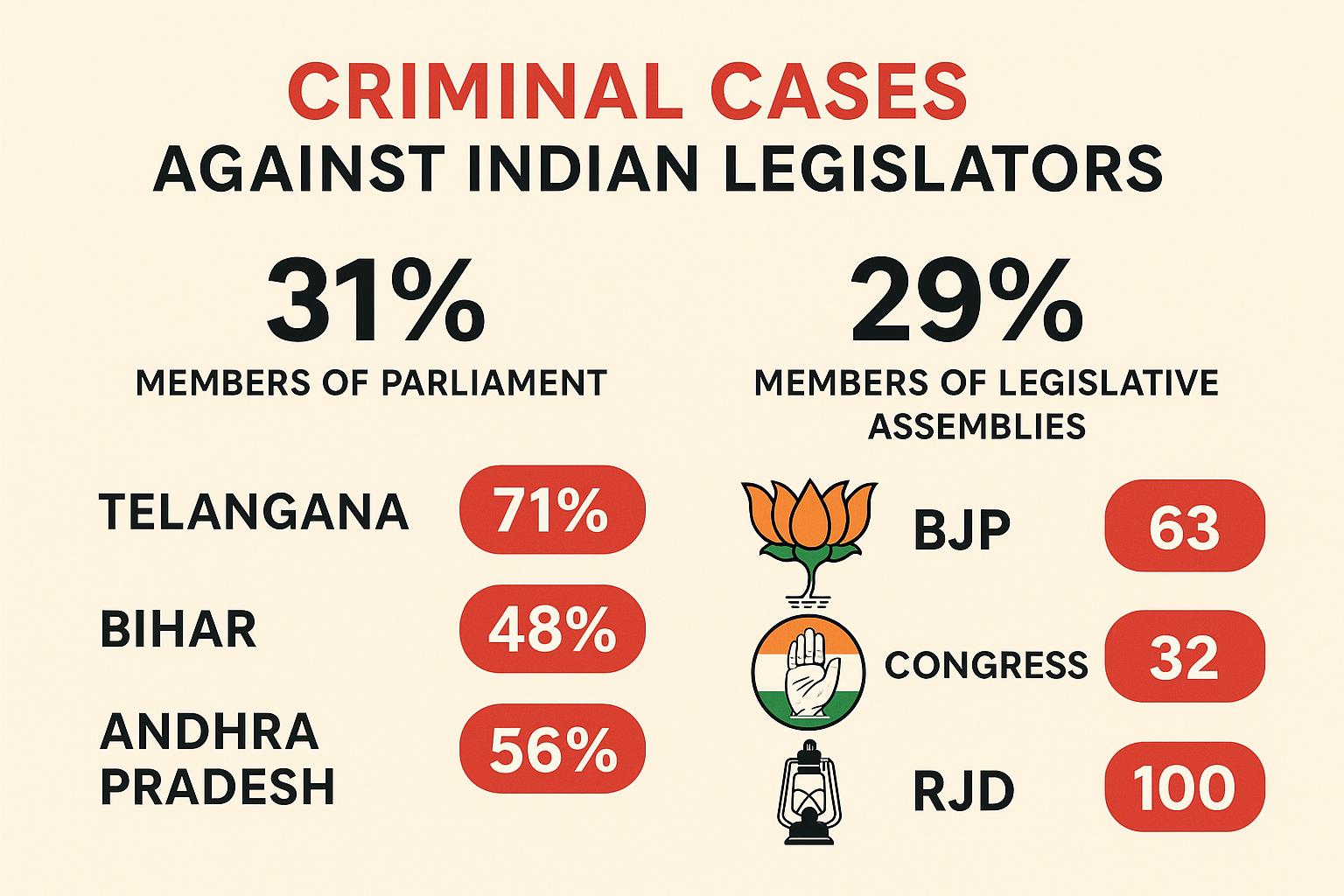

Context: A recent analysis of India’s elected representatives reveals a deeply troubling trend: 31% of Members of Parliament (MPs) and 29% of Members of Legislative Assemblies (MLAs) have declared serious criminal cases against them which signifies a sharp increase from 14% of MPs in 2009.

What is the Criminalisation of Politics?

The criminalisation of politics refers to the increasing infiltration of individuals with pending criminal charges into the political sphere, often leading to their election to legislative bodies. It is a two-fold problem:

- Criminals entering politics: Individuals with criminal backgrounds contesting elections to gain influence, escape the law, or manipulate policy for personal gain.

- Politicians turning criminal: Elected representatives using their power and resources to commit crimes or shield themselves from prosecution.

How does it affect the Rule of Law and Policy-making?

(a) Impact on Rule of Law:

- Erosion of Public Trust: When the law-makers are themselves alleged law-breakers, it shatters public faith in the justice system and democratic processes.

- Obstruction of Justice: These representatives often use their political clout to intimidate investigators, influence witnesses, and delay trials, effectively placing themselves above the law.

- Criminalisation of the State Apparatus: They can politicise and corrupt the police and bureaucracy, turning public servants into personal enforcers and crippling the state’s capacity to uphold law and order impartially.

(b) Impact on Policy-Making:

- Distorted Policy Priorities: Policy-making may be skewed to serve the interests of these representatives and their associates rather than public welfare.

- Disruption of Democratic Functioning: Such MPs/MLAs often use threats and intimidation in legislative houses, leading to dysfunctional legislatures where debate is stifled and coercion reigns.

- Poor Quality of Governance: The focus shifts from development and public service to patronage, rent-seeking, and consolidating power through illicit means.

What measures can be taken to curb it?

(a) Judicial Measures:

- Fast-Track Courts: Establish exclusive fast-track courts to adjudicate criminal cases against MPs and MLAs within a strict timeframe (e.g., one year).

- Lifetime Disqualification: The Supreme Court, in Lily Thomas v. Union of India (2013), struck down a provision that protected convicted lawmakers from immediate disqualification if they appealed. A stronger measure debated is lifetime disqualification upon conviction, not just the current six-year ban.

(b) Legislative Reforms:

- Amending the RPA, 1951: The Law Commission’s 179th Report (1999) and 244th Report (2014) have recommended amending the Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951, to disqualify persons against whom charges have been framed in serious offences from contesting elections.

- Decriminalisation of Politics: A bill proposing that any person charged with a serious offence be debarred from contesting has been discussed but not passed, due to concerns over its potential for misuse through frivolous cases.

(c) Electoral Reforms:

- Internal Party Democracy: Mandating transparent processes for candidate selection through primaries or internal elections, rather than leaving it to the whims of party leadership.

- Role of ECI: Empowering the Election Commission of India (ECI) to de-register political parties that repeatedly give tickets to candidates with serious criminal backgrounds.

- Informed Electorate: Voter awareness campaigns, like those by the ADR, to put pressure on political parties to clean up their candidate lists. The NOTA (None of the Above) option is a tool, though largely symbolic.

- In Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) v. Union of India (2002) case, Supreme Court made it mandatory for all candidates contesting elections to file an affidavit disclosing their criminal records, educational qualifications, and financial assets.