Font size:

Print

Assisted Dying Bill Passed by UK Parliament

U.K. MPs approve Assisted Dying bill

Context: Recently, the UK House of Commons has passed the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, which now moves to the House of Lords for further scrutiny and possible amendments before becoming law.

What is the Eligibility and legal procedure?

- Eligibility Requirements: Applicants must be 18 or older, residents of England or Wales, registered with a GP for at least 12 months, diagnosed with a terminal illness (life expectancy of six months or less), and possess the mental capacity to decide.

- Voluntary Declarations: Individuals must make two formal, witnessed declarations of their wish to die, spaced at least seven days apart.

- Medical Assessments: Two independent doctors must evaluate and confirm the patient’s eligibility and mental capacity.

- Procedure & Safeguards: After approval, a 14-day waiting period follows. A doctor prepares the life-ending medication, but the individual must self-administer it.

- Legal Protections: Coercing or pressuring someone into assisted dying is a criminal offence, punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

What is people’s reaction?

- Patients and their families support the bill because they believe it helps spare loved ones from prolonged and unbearable suffering.

- Campaign groups argue that the proposed safeguards are “rigorous and safe,” ensuring responsible implementation.

- Some clinicians support the bill, stating that it promotes honest, transparent, and patient-centred palliative care planning.

- Opponents—including disability-rights advocates, religious leaders, and some doctors and politicians—argue that the bill may exert subtle pressure on vulnerable people, undermine the sanctity of life, strain National Health Service (NHS) resources, and potentially expand beyond its intended scope.

How does the UK fit into global practice?

- If enacted, England & Wales would join jurisdictions such as Canada, Belgium, Australia, New Zealand and ten U.S. states with similar assisted‑dying frameworks, while remaining distinct from countries (e.g., Netherlands) that allow doctor‑administered euthanasia.

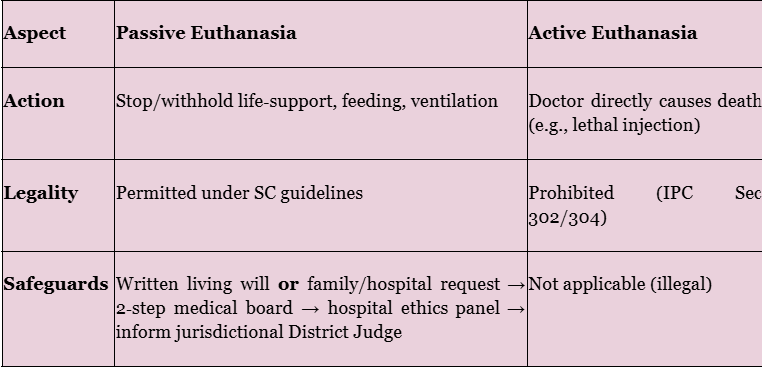

What is the legal status of euthanasia in India?

Which Supreme Court rulings shaped the law?

- Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug v. Union of India (2011) – first recognised passive euthanasia for patients in a permanent vegetative state; required High‑Court approval and a medical board.

- Common Cause v. Union of India (9 March 2018) – declared the “right to die with dignity” a facet of Article 21 and allowed living wills/advance directives for competent adults.

- SC Order (24 January 2023) – simplified the 2018 procedure: no magistrate signature, quicker twin‑board medical review, and e‑registry of living wills.

What safeguards govern passive euthanasia today?

- A living will be signed before two witnesses and attested by a notary/gazetted officer.

- Primary medical board (treating hospital) + secondary, independent board must each unanimously certify: irreversible illness, no hope of recovery, and patient’s prior wish.

- Time‑bound: Boards must act within 48 hours; decision communicated to patient’s family and hospital. These 2023 tweaks replaced the earlier high‑court route, making end‑of‑life decisions faster yet still court‑supervised.

Why is the UK debate relevant for India?

- Policy spill‑over: A UK‑style assisted‑dying framework (self‑administered lethal medication) would go beyond India’s passive model and reopen constitutional, ethical and religious questions.

- Legislative vacuum: Despite two Law Commission reports, Parliament has yet to codify end‑of‑life law. The Supreme Court’s guidelines thus remain the de facto statute.

- Public opinion & palliative care gaps: As palliative‑care access remains uneven, critics warn that introducing assisted dying without first improving hospice services could pressure the vulnerable—an argument that mirrors UK opponents’ concerns.