Nobel Prize in Literature 2025 – Laszlo Krasznahorkai

Discover the life and art of Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai, winner of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature. Explore how his long, poetic sentences, dark humour, and vision of endurance transform chaos into meaning and reaffirm the power of art in an uncertain world.

Introduction

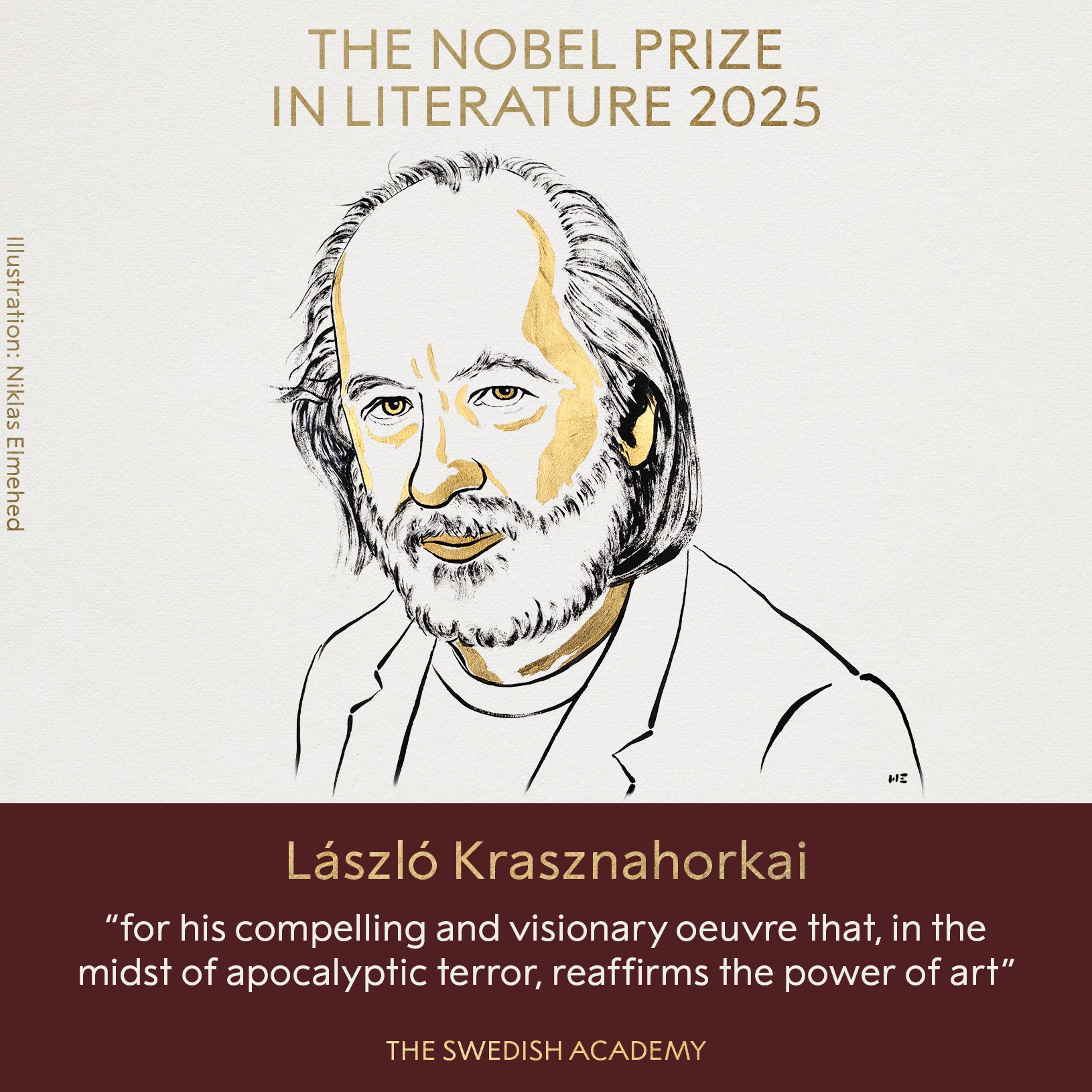

In 2025, the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to László Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian novelist celebrated for his long, meditative sentences and his bleakly comic vision of the world. Often called “the Hungarian master of the apocalypse,” Krasznahorkai writes about chaos, despair, and the fragile beauty that survives within them. The Swedish Academy praised him for his “compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.”

As Aishwarya Khosla notes in her article “The Long Sentence of the World: Who is László Krasznahorkai — Winner of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature” (The Indian Express, 9 October 2025), his fiction combines despair, absurdity, and fleeting grace, transforming apocalypse from a single catastrophic event into a lasting condition of human endurance and spiritual transcendence. The Nobel Prize therefore recognised not only his lifetime of artistic achievement but also his belief that life, art, and politics are bound together in an endless struggle between hopelessness and the possibility of redemption.

To understand how such a vision was formed, it is essential to look at the life that shaped it. Behind Krasznahorkai’s vast, meditative sentences lies a personal history of resistance and restlessness — a life lived against conformity and control.

A Life Against Conformity

Born in 1954 in the small town of Gyula, Hungary, Krasznahorkai grew up under Soviet control, in a society where freedom of speech and creativity were closely watched. As a young man, he worked odd jobs — a miner, a night watchman, a cultural-house director — while secretly reading writers such as Franz Kafka, Malcolm Lowry, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. These influences shaped his belief that real life was not in comfort or power but in “the poorest villages,” where truth and suffering coexist.

He often described his youth as a search for meaning amid chaos. His first novel, Satantango (1985), written during communist Hungary, told of a rain-soaked village full of con artists and dreamers. Against all odds, it was published, despite being — as he said — “anything but an unproblematic novel for the Communist system.” In that moment, his life as a writer of resistance began.

This spirit of defiance and perseverance runs through all his later work. Having lived through political repression and personal uncertainty, Krasznahorkai came to see endurance as the truest form of strength. His fiction reflects this belief — that even when the world seems absurd or hopeless, one must continue, breath by breath, word by word.

Attitude to Life: Endurance through Absurdity

Krasznahorkai’s novels are full of people who live on the edge of ruin — drunkards, archivists, failed philosophers, and lonely wanderers. Yet he does not pity them. Instead, he gives them dignity. As his translator George Szirtes said, even his “miserable people” possess a strange grace. For Krasznahorkai, life is absurd, yes — but it must still be lived, sentence by sentence, with courage.

In interviews, he often spoke about how human beings exist “in the middle of an apocalypse.” For him, this does not mean the end of the world in fire and thunder, but the slow collapse of meaning in everyday life. When social systems fall apart, when truth and morality crumble, he sees apocalypse as a process — an ongoing condition. “The apocalypse is now,” he said, “an ongoing judgment.” In such a world, the task of the artist is not to offer comfort but to hold chaos together through art — even if only “by a comma.” By this phrase, Krasznahorkai means that even the smallest act of artistic creation — a pause, a mark, a moment of attention — can keep disorder from completely consuming meaning. The comma, for him, symbolises persistence: the decision to continue the sentence, to keep going when despair tempts silence. This patient endurance, this stubborn belief that beauty still matters amid ruin, defines his attitude to life.

It is this very philosophy that shapes the rhythm and structure of his writing. Krasznahorkai’s belief in endurance translates directly into his prose style, where the act of continuing — of refusing to end the sentence — becomes a metaphor for surviving chaos.

Poetics: The Music of Endless Sentences

Krasznahorkai’s prose is famous — and sometimes feared — for its length. Some of his novels unfold in a single unbroken sentence that can last for pages, even hundreds of them. His 2021 novel Herscht 07769, for instance, contains only one full stop in 400 pages. This style reflects the rhythm of human thought — restless, circling, unstoppable. He once said that he writes this way because “when you want to say something very important, you don’t need full stops but breaths and rhythm — rhythm and melody.”

These sentences do not simply show confusion; they recreate the experience of living in a world where nothing stays still. Reading his books can feel like being swept away by a river — the meaning is not always clear, but the movement is powerful. Critics have compared his style to music, describing it as complex, patterned, and spiritual. Much like a piece of classical music that repeats and deepens with each note, his writing builds layer upon layer of emotion and thought. The result is an atmosphere that feels both intense and strangely calming, where rhythm and repetition replace traditional storytelling.

Krasznahorkai described writing as a ritual. For him, art was not about explaining the world but about participating in it — word after word, sentence after sentence. “Writing is a ritual you perform,” he said, “not for theology, but for the act itself.” In this sense, his poetics are also his philosophy: art becomes a form of endurance, a quiet rebellion against meaninglessness.

Yet even within this solemn vision, Krasznahorkai allows space for humour — a dark, ironic laughter that keeps despair from turning into defeat. His ability to find comedy within tragedy shows that endurance is not only about survival but also about perspective: the strength to recognise absurdity and still continue.

Humour in Despair

Though often labelled as dark or difficult, Krasznahorkai’s fiction is also deeply funny. His humour is slow, dry, and tragic — what one critic called “mordant humour.” In Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming (2016), a disgraced aristocrat returns to his hometown, where gossiping villagers and mad philosophers create chaos. The novel, while full of nihilism, is also “deeply funny.” As one reviewer said, it is “a dance of death and laughter.” This mixture of tragedy and comedy — where despair turns into absurd laughter — is what makes his vision human rather than hopeless.

This sharp awareness of absurdity also shapes Krasznahorkai’s view of society and power. His laughter, though often subdued, is not merely for amusement — it exposes the madness of authority, the foolishness of conformity, and the fragility of human systems. Beneath his humour lies a quiet but fierce moral resistance, a conviction that art must speak truth to power, however indirectly.

Politics: Speaking Against Power

Krasznahorkai’s relationship with politics is complex. He insists that he does not write about politics, but from within its consequences. His books explore the ways ordinary people live under systems that crush individuality — whether the Communist regime of his youth or the populist governments of today.

He has openly criticised Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, calling his regime “a psychiatric case” for claiming neutrality during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. For Krasznahorkai, neutrality in the face of violence is moral blindness. “How can a country be neutral when the Russians invade a neighbour?” he asked angrily. He refuses to accept indifference or silence as moral positions.

His fiction mirrors this conviction. In War & War (1999), a lonely archivist tries to preserve a mysterious manuscript online before taking his own life — a haunting symbol of humanity’s wish to save meaning before it disappears. In The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), a circus brings a stuffed whale and chaos to a small town — an allegory for political manipulation and mass hysteria. Through such metaphors, Krasznahorkai reveals how fear and propaganda distort reality.

At the same time, he resists the idea of grand politics. As he told The New York Times, “He doesn’t deal with grand politics; he’s dealing with the experiences of people who live within societies that are decaying.” His focus is on the small, the broken, the everyday. Through these, he uncovers universal truths about power and vulnerability.

It is precisely this attention to the fragile and the ordinary that shapes his deepest conviction — that even amid decay, art endures. For Krasznahorkai, creativity is not a political statement in itself but a form of quiet resistance, a way of preserving meaning when the world threatens to erase it.

Faith in Art

Despite his bleak vision, Krasznahorkai remains an optimist about art itself. The Nobel Committee praised him for reaffirming “the power of art in the midst of apocalyptic terror.” His writing shows that beauty can exist even in destruction, and that language, when used with care, can still create order from chaos. This belief aligns him with earlier Nobel laureates such as Czesław Miłosz and Seamus Heaney, who also transformed national trauma into universal art.

For Krasznahorkai, this faith in art is not a lofty ideal but a lived truth — a way of surviving chaos with grace. His commitment to beauty and language stands as a form of endurance, a quiet defiance against despair and decay. It is fitting, then, that when asked about the honour that crowned his long career, his response was marked by simplicity and calm. When asked how he felt about winning the Nobel, he replied simply, “I am calm and very nervous … I don’t know what’s coming in the future.” His humility reflects his lifelong attitude: a quiet awareness that all human achievement, even the greatest, is temporary. But art, unlike politics, can last.

This enduring belief in art’s power to reveal truth also led Krasznahorkai beyond the borders of Europe, both geographically and spiritually. His search for meaning, once rooted in the ruins of post-Communist Hungary, gradually expanded toward a global and philosophical vision. Through travel and reflection, he found new sources of wisdom in the East — where silence, stillness, and repetition held the same depth that language once did for him.

Between East and West

Krasznahorkai’s later works reveal his fascination with Eastern philosophy, especially Buddhism and Japanese aesthetics. In Seiobo There Below (2008), he describes moments of artistic perfection — a Buddha statue being restored, a heron hunting, a Noh actor rehearsing — all glimpses of transcendence amid impermanence. These scenes suggest that beauty is fleeting but real. His A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East (2022) reads like a meditation, a prose poem in praise of silence. Through these works, he bridges East and West — European despair and Eastern calm — showing that art can be both suffering and salvation.

Conclusion: The Long Sentence of the World

László Krasznahorkai’s fiction is demanding, but it rewards those who stay with it. His attitude to life is stoic yet compassionate: to face despair without denial. His poetics convert chaos into rhythm, turning the sentence into an instrument of endurance. His politics resist tyranny and indifference alike, reminding us that silence helps power, and that art must speak, however softly.

To read Krasznahorkai is to experience the world not as a series of fragments but as one long, trembling breath — tragic, comic, terrifying, and beautiful. Each clause, each comma, each patient continuation becomes a declaration that the world, though broken, is still worth describing. And so the sentence goes on, as life goes on: uncertain, imperfect, but alive.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH