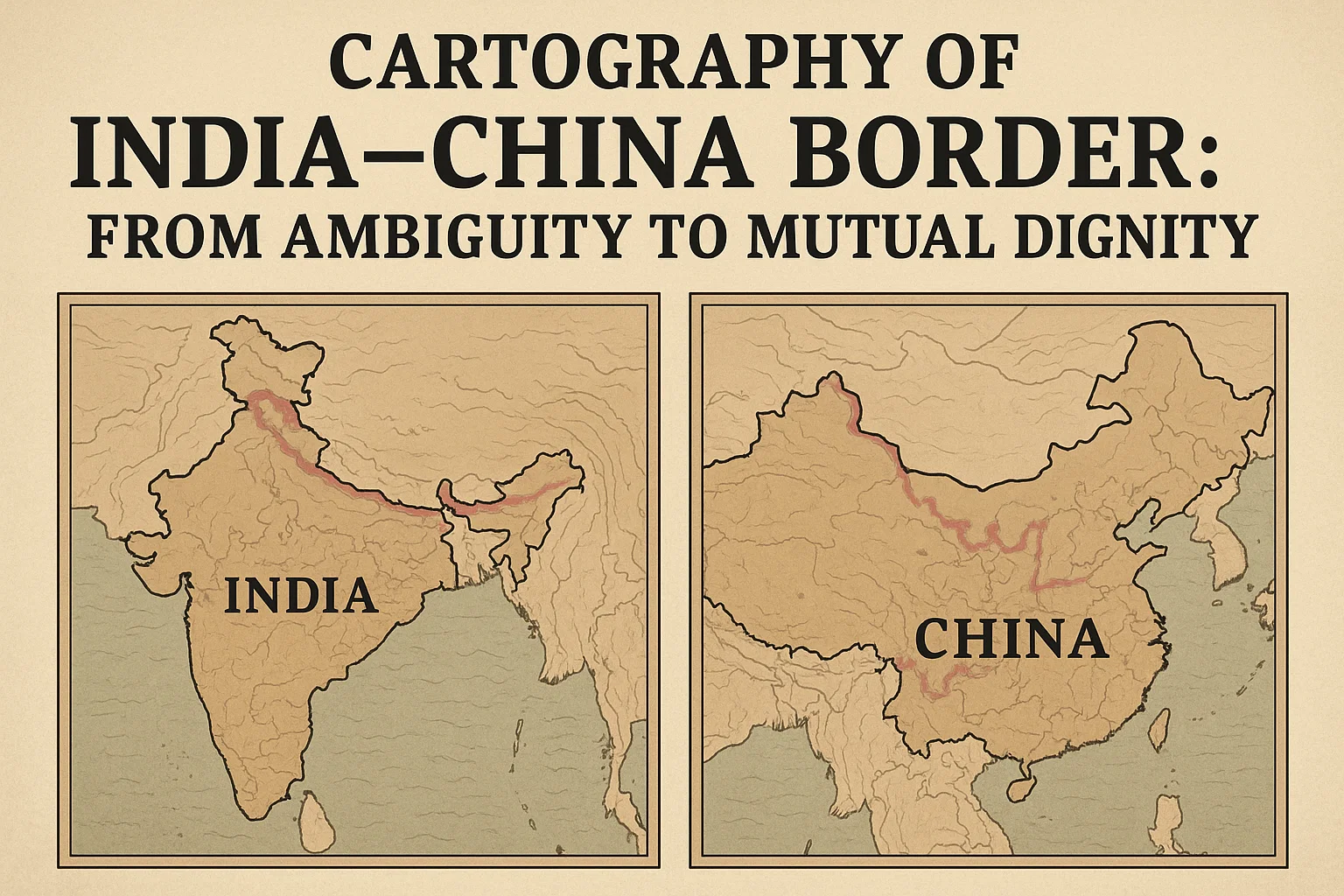

Cartography of India–China Border: From Ambiguity to Mutual Dignity

Explore the history of India–China border cartography, from Manchu maps to modern disputes, and why pragmatic diplomacy matters more than maps alone.

Introduction

In his article “The Mapping of the India-China Border” (The Hindu, 24 September 2025), Sunil Khatri challenges Manoj Joshi’s earlier assertion that the India–China border has never been properly defined. By revisiting Manchu imperial maps of 1721 and 1761 and later alignments in 1899 and 1914, Khatri maintains that the boundary was historically clear, and that later Chinese claims of ambiguity are political inventions rather than reflections of fact. This essay evaluates Khatri’s contention through an analytical lens, arguing that while historical cartography does support India’s case, the durability of any resolution lies less in map evidence and more in pragmatic diplomacy. The analysis proceeds by reviewing the historical record, examining the nature of cartographic authority, and considering the political consequences of claims made by both sides.

Historical Foundations

Two major maps prepared during the Manchu rule stand out for their precision: Emperor Kang-hsi’s map of 1721 and Emperor Ch’ien-lung’s map of 1761, both drawn with Jesuit assistance. The 1721 map limited Tibet’s boundary to the northern side of the Himalayas, excluding Tawang and the tribal belt of present-day Arunachal Pradesh. Similarly, the 1761 map did not extend Eastern Turkestan south of the Kunlun range, leaving Aksai Chin outside Chinese imperial conception. These records suggest that the contested regions were never historically within China’s territorial reach. The Simla Conference of 1913–14 reinforces this view, as the Republic of China’s delegate explicitly acknowledged Tibet had no claim to lands south of the Himalayas. On this basis, the Indo-Tibetan alignment of 1914 and the Kashmir–Sinkiang alignment of 1899 emerge as defensible borders for modern India.

Authority of Maps

The reliance on cartographic authority raises an essential question: how definitive are maps as instruments of sovereignty? While they present coordinate lines with precision, maps also reflect the interests of those who commission them. Joshi’s critique—though not quoted directly—likely rests on this concern: maps are not neutral records, especially when produced under imperial power structures. Moreover, the gap between mapped lines and actual control can be wide. The Manchu legacy, while significant, cannot by itself serve as the final arbiter of territorial legitimacy. In international law, treaties, control, and recognition by states carry equal weight. This dual nature—scientific precision on one hand and political assertion on the other—makes maps a contested basis for settling borders.

Chinese Revisions

The Republic of China’s decision in the 1940s to discard the Manchu territorial bequest marked a turning point. The 1943 map, admitted by its own authors to be “an unprecise draft,” was followed by another in 1947, coinciding with India’s vulnerable post-independence moment. After 1949, the People’s Republic of China absorbed these cartographic innovations into its national narrative. Chou En-lai’s admission to Jawaharlal Nehru in 1954 that old maps were being reprinted did not soften territorial ambition. By 1960, Chou attempted to shift the discussion away from documents toward a “set of principles” for negotiation. This manoeuvre was less a concession than a strategic repositioning: moving debate from evidence, where China’s case was weaker, to principles, where flexibility was greater. Such tactics reveal a deliberate evolution of claims—away from historical inheritance and towards politically useful reinterpretations.

Indian Counter-Claims

India, by contrast, has leaned on precisely those alignments and maps that China tends to sidestep. Anchoring its position in the 1899 and 1914 arrangements, New Delhi asserts that its borders are rooted in historical continuity and validated by Chinese representatives of the time. Yet the challenge lies in translating documentary strength into geopolitical security. The 1962 war exposed this gap: India’s stronger historical case could not prevent military setbacks in Aksai Chin. Similarly, China’s refusal to accept the McMahon Line in Arunachal Pradesh has sustained cycles of standoffs. Emphasising historical cartography highlights India’s legitimacy but risks leaving its claims as moral victories unless backed by enforceable power.

Negotiated Pragmatism

In this light, the need for a “package deal” becomes evident. Any durable solution must rest on mutual dignity, equitable adjustment, and likely acceptance of the 1899 and 1914 alignments, with room for limited territorial swaps. As former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale has noted, principle-based frameworks often conceal traps, but documents alone cannot guarantee peace. International politics is shaped as much by compromise as by entitlement. A pragmatic arrangement—such as safeguarding Arunachal Pradesh while conceding limited ground in Aksai Chin—could secure stability, even if politically difficult. Such an approach might release both nations from perpetual confrontation and redirect attention towards broader developmental concerns.

Persistent Ambiguity

Despite the appeal of pragmatic solutions, ambiguity remains entrenched. China benefits from leaving borders unresolved, enabling periodic pressure on India without committing to final settlement. India, meanwhile, risks appearing rigid if it insists exclusively on historical legitimacy. Domestic politics compounds the problem: China’s leadership cannot renounce claims woven into nationalist identity, and Indian governments cannot easily justify concessions. Thus, historical clarity does not automatically translate into political resolution. Continued standoffs in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh demonstrate that the problem is as much about shifting power balances and mistrust as it is about cartography.

Conclusion

Sunil Khatri’s essay provides an important corrective to narratives that portray the India–China border as historically undefined. The Manchu maps of 1721 and 1761, together with the alignments of 1899 and 1914, offer strong evidence that India’s case rests on firmer historical ground than China’s. However, the authority of maps, though powerful in argument, is insufficient in isolation. Manoj Joshi’s scepticism—whether overstated or not—reminds us that sovereignty cannot be secured by cartography alone. As history shows, China has deliberately revised its claims, and India has struggled to enforce its rightful boundaries. The path forward lies not in debating maps indefinitely but in forging a negotiated settlement that balances historical legitimacy with pragmatic compromise. Such an outcome would not erase past disputes, but it could transform the border from a theatre of perpetual ambiguity into a boundary of mutual dignity.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH