Fragile Peace at the India-China Border

Analysing insights on the India-China border dispute—agreements, weaknesses, and the path toward lasting peace and clarity.

Setting the Scene

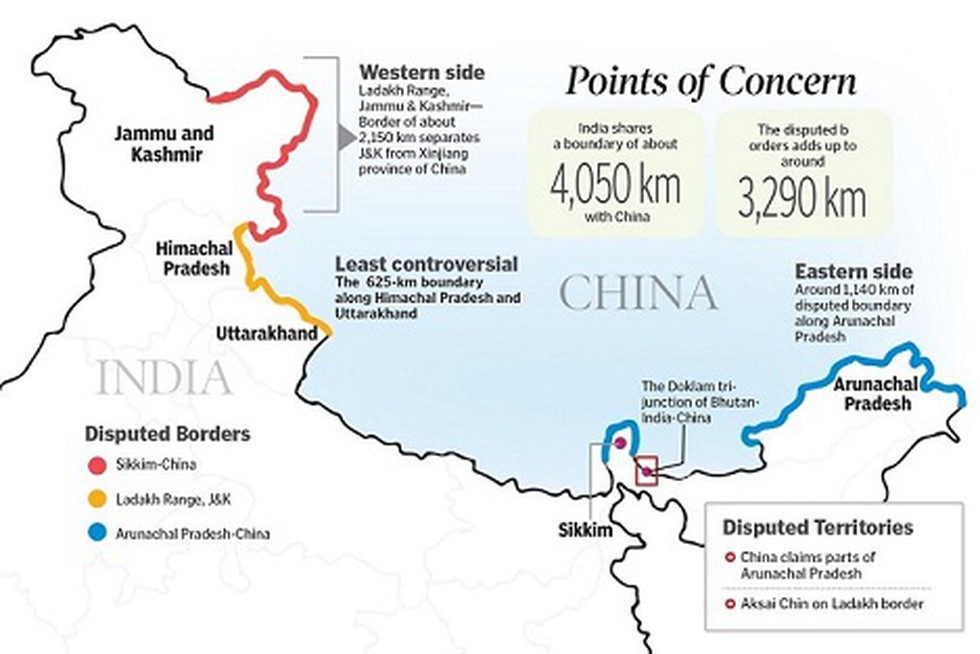

Manoj Joshi, in “India-China: The Inability to Define a Border” (The Hindu, September 08, 2025), explains that the India-China border dispute is one of the most persistent territorial conflicts in modern times. It centres mainly on two areas: Aksai Chin in the west and Arunachal Pradesh in the east. Both nations claim these territories based on old maps, political interests, and strategic needs. Over the years, the dispute has shaped the relationship between the two Asian giants and influenced wider regional stability. Joshi shows how diplomatic talks, peace agreements, and confidence-building measures have sought to manage tensions, but clashes and mistrust continue to define the border. He argues that while peace agreements like the 1993 Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement (BPTA) and the 1996 military confidence-building measures provided a structure for dialogue, their limitations highlight the urgent need for clearer definitions, stronger mechanisms, and consistent political will from both sides. Therefore, the central claim of this essay is that lasting peace between India and China will only be possible when both nations move beyond temporary arrangements and establish a clearly defined border supported by trust and consistent commitment.

The Promise of Agreements

Joshi notes that the central idea behind India-China border relations is that peace is possible only when both sides agree to respect the Line of Actual Control (LAC). This is the practical border recognised by both nations, though not formally settled. Without a shared understanding of where the border lies, clashes are inevitable.

He traces how Rajiv Gandhi’s 1988 visit to Beijing opened a new phase of dialogue after decades of hostility. The creation of the Joint Working Group (JWG) allowed military and political leaders to talk directly. These talks resulted in the 1993 BPTA, which prohibited the use of force, required withdrawal if soldiers crossed the LAC by mistake, and encouraged joint checks in disputed areas. The 1996 follow-up agreement went further, limiting troops, heavy weapons, and large military exercises near the LAC. Together, these agreements embodied the hope that peace could be achieved by freezing the situation at the border while broader ties improved.

Yet Joshi also stresses that the promise of these agreements rests on fragile ground. Chinese troops enjoy easier access to the border due to roads across the Tibetan plateau, while Indian troops face long, difficult journeys through mountains. This imbalance makes trust harder to maintain. Moreover, the agreements assumed both sides would faithfully follow rules and exchange maps to clarify the LAC. But when attempts to trade maps in 2002 failed within minutes, it showed that both nations remained trapped in their maximalist positions. Thus, the claim that peace depends on recognising and respecting the LAC holds true in theory but is undermined by poor execution and strategic rivalry.

Gaps and Weaknesses

Joshi carefully points out that agreements, while important, are not perfect solutions. They contain gaps, weaknesses, and challenges that continue to haunt the border.

One key weakness is that the LAC itself has never been fully defined. While both sides agreed in the 1990s to exchange maps, they only succeeded in the central sector, which was less controversial. The eastern and western sectors, however, contained many hotspots—such as Pangong Tso, Depsang, and Demchok—where perceptions of the border differed sharply. This lack of clarity meant that agreements could not prevent troops from coming face to face in disputed zones.

Another weakness Joshi highlights is that peace depends not only on documents but also on trust, infrastructure, and political will. For example, he recalls how China’s violation of the 1996 accord in 2020, when it carried out large military exercises near Ladakh, proved that even signed agreements can be disregarded when national strategy demands. Similarly, while India values Arunachal Pradesh as vital for its unity and defence, China sees Aksai Chin as part of its Xinjiang region. These deep strategic stakes make compromise difficult.

These gaps show that agreements are necessary but not sufficient. They reduce risks, slow escalation, and create dialogue channels, but they cannot replace a final boundary settlement. Both sides know this but have often chosen to delay resolution, hoping time will strengthen their positions. As a result, the border remains a flashpoint despite decades of diplomacy.

Paths Forward

Joshi recommends strengthening mechanisms to prevent small disputes from escalating into major clashes. One major lesson is the need for clarity. Without a mutually accepted definition of the LAC, face-offs will continue. Renewed efforts to exchange and verify maps, perhaps with the involvement of neutral observers or technology-based monitoring, could reduce uncertainty.

He also stresses the need to expand confidence-building measures beyond troop limits. For instance, both nations could establish more frequent hotlines between local commanders, create joint patrol protocols, and conduct coordinated humanitarian exercises in border regions. These measures would build trust and reduce the chance of misinterpretation during tense situations.

Joshi further argues for balancing strategic interests with broader cooperation. Despite disputes, both India and China have strong reasons to avoid open conflict. Trade, technology exchange, and regional leadership all depend on stability. Past actions, like reopening consulates and resuming border trade in the 1990s, show that practical cooperation can continue even with an unresolved border. Building on such measures could create goodwill and a better environment for eventual settlement.

Finally, Joshi points out that leadership plays a decisive role. When political leaders invest in dialogue—as Rajiv Gandhi and Narasimha Rao did—progress is possible. A renewed high-level commitment, supported by consistent follow-up, is essential for peace. Without it, even well-designed agreements risk becoming hollow.

Looking Ahead

Joshi concludes that the India-China border dispute is a long-standing conflict shaped by history, geography, and national strategy. The agreements of the 1990s provided a framework for peace by recognising the LAC and limiting military risks, but their incomplete implementation and the failure to define the border have left tensions unresolved. Peace, he argues, depends on clarity, trust, and cooperation, yet these remain fragile. For India and China, the way forward lies in turning temporary arrangements into lasting solutions. This requires renewed political will, stronger mechanisms, and a commitment to seeing the border not as a battlefield but as a bridge for cooperation. The choices both nations make will not only shape their bilateral ties but also the stability of Asia as a whole.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH