Gupta Empire: Golden Age of Ancient India

Study the Gupta Empire for UPSC – its rulers, polity, economy, society, religion, art, literature, and reasons for decline.

The Gupta Empire, known as the Golden Age of Ancient India, is important for UPSC as it marks a peak in India’s cultural, scientific, and political development. This period saw major advancements in literature, art, mathematics, and architecture, making it relevant for both Prelims and GS Paper I in Mains. Its contributions to polity, economy, and cultural heritage also enrich essay writing and interview responses, making it a high-scoring and frequently asked topic in the exam

Introduction

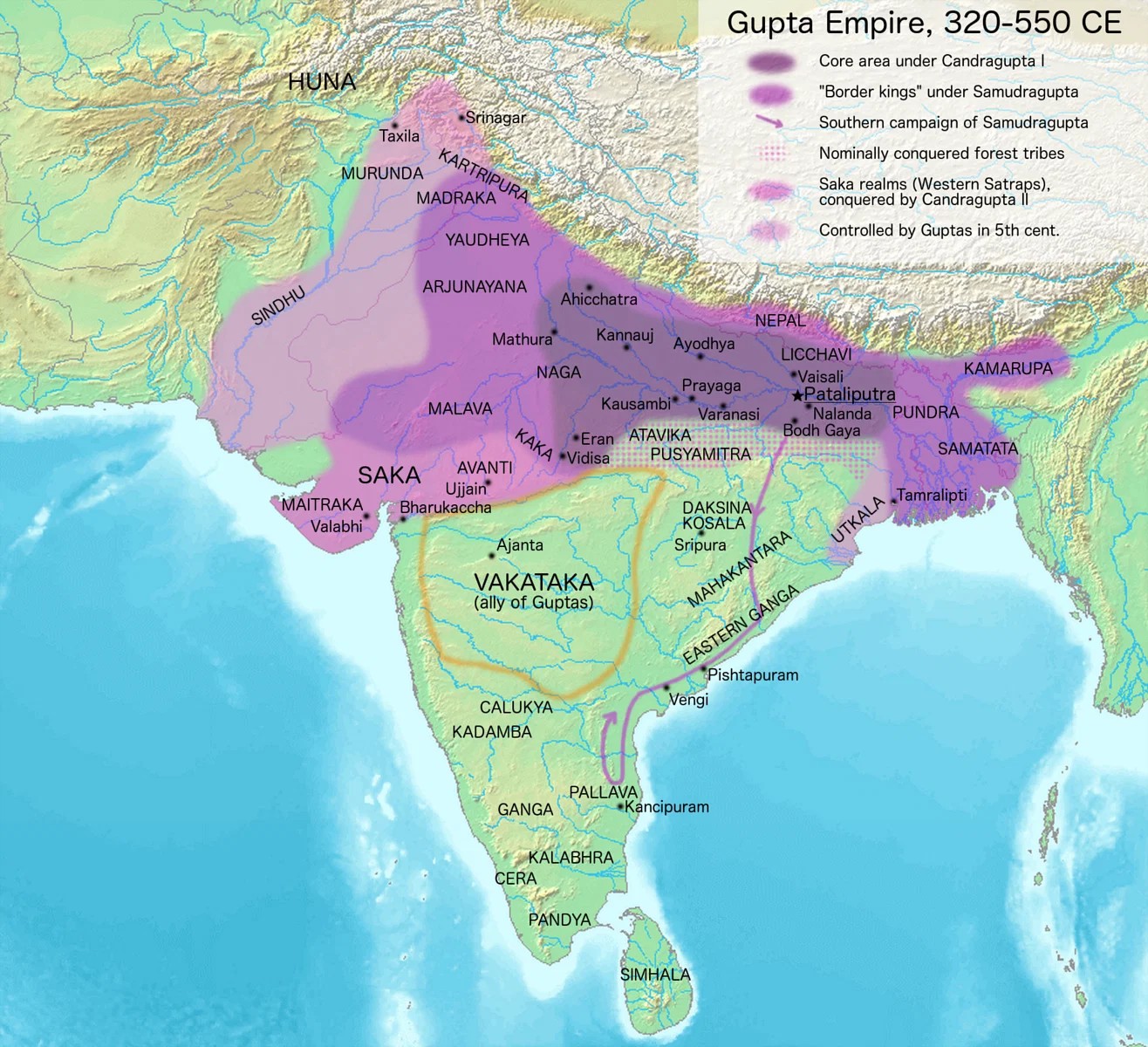

After the decline of the Maurya Empire, two major powers emerged: the Satavahanas in the Deccan and south India, and the Kushans in the north. The Satavahanas brought political stability and economic prosperity to the southern regions, largely through active trade with the Roman Empire. Similarly, the Kushans played a stabilising role in northern India. However, by the mid-3rd century CE, both empires had declined. The Gupta Empire rose to prominence on the remnants of the Kushan domain, gaining control over much of their former territory.

The Gupta dynasty was established by Shrigupta, who probably belonged to the vaishya

caste. He hailed from either Magadha (Bihar) or Prayaga (eastern U.P.). His son

Ghatotkacha, who carried the title of maharaja, appears to be some small king about

whom nothing much is known. Although the Gupta Empire was not as extensive as the Mauryan, it achieved political unification of north India between AD 335 and 455. The early Gupta kingdom covered parts of present-day Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, with UP playing a more prominent role, evidenced by the abundance of coins and inscriptions. Prayag (modern Allahabad) is considered the nucleus of Gupta power, from where they expanded their influence across the surrounding regions.

Rise of the Gupta Empire

- The Guptas likely began as vassals of the Kushans in Uttar Pradesh and took over their rule without much delay.

- They adopted several elements from the Kushans, such as saddles, reins, buttoned coats, trousers, and boots, which improved their cavalry and mobility.

- The Gupta military strength was centered on cavalry, similar to the Kushans, with horsemen depicted on their coins. Although some kings were praised as chariot warriors, horses were their main strength.

- Their core region was the fertile Madhyadesh (modern Bihar and UP), which provided a strong agricultural base.

- They utilised the iron resources of central India and southern Bihar for economic and military advantage.

- Their location near northern trade routes, particularly those involved in the silk trade with the Byzantine Empire, further enhanced their prosperity.

- The Guptas initially extended their rule over Anuganga (mid-Gangetic plain), Prayag (Allahabad), Saketa (Ayodhya), and Magadha, later expanding into a pan-Indian empire.

- Following the decline of Kushan rule around AD 230, the Murundas (possibly Kushan relatives) ruled parts of central India until AD 250. Around AD 275, the Guptas rose to power.

Important Rulers of the Gupta Empire

1. Chandragupta I (c. 320–335 CE)

Chandragupta I was the founder of the Gupta Empire and the first notable ruler of the dynasty. He adopted the imperial title Maharajadhiraja (king of kings), signifying supreme authority. His reign marks the beginning of the Gupta Era in 319–320 CE, likely coinciding with his coronation.

-

He expanded his territory to include parts of Bihar, eastern Uttar Pradesh, and Bengal, with Pataliputra as the capital.

-

His marriage to Kumaradevi, a Lichchhavi princess from Nepal, was a significant political alliance. It enhanced the status of the Guptas, who were probably of the Vaishya class, by aligning them with the Kshatriya Lichchhavis.

-

Joint coinage was issued in the names of Chandragupta I, Kumaradevi, and the Lichchhavis, emphasising the importance of this alliance.

-

His son, Samudragupta, was referred to as Lichchhavi-dauhitra (grandson of the Lichchhavis) in the Allahabad Prashasti inscription.

2. Samudragupta (c. 335–380 CE)

Samudragupta, son of Chandragupta I, is regarded as one of ancient India’s greatest military strategists. He pursued an expansionist policy and is often referred to as the “Napoleon of India.”

-

His conquests and achievements are recorded in the Allahabad Pillar inscription, composed by his court poet Harishena.

-

He subdued multiple regions and rulers:

-

Princes of the Ganga–Yamuna Doab: Defeated and their lands annexed.

-

Eastern Himalayan and frontier states, including Nepal, Assam, Bengal, and republics of Punjab, were subdued.

-

Forest kingdoms (Atavika Rajyas) in central India were brought under control.

-

Southern India: Twelve kings were defeated and reinstated as tributary rulers; the Pallavas of Kanchi acknowledged his supremacy.

-

Shakas and Kushans in north-western India and parts of Afghanistan were defeated or made subordinate.

-

-

He received international recognition—Meghavarman, the king of Sri Lanka, sought his permission to construct a Buddhist monastery at Gaya, which was granted.

-

He issued gold coins in large numbers and patronised art, music, and learning.

-

The Allahabad inscription describes him as undefeated in battle and highlights his vast empire, which extended beyond traditional Indian frontiers.

3. Chandragupta II (c. 380–412 CE)

Chandragupta II, also known by the title Vikramaditya, presided over the apex of Gupta political and cultural power.

-

He cemented a strategic alliance by marrying his daughter Prabhavatigupta to a Vakataka prince. After her husband’s death, she ruled as regent, allowing Chandragupta II to exert indirect influence over the Deccan.

-

He captured Mathura from the Kushans and defeated the Shaka Kshatrapas of Malwa and Gujarat, ending their centuries-old rule.

-

The annexation of the western coastal regions enhanced overseas trade and commercial wealth.

-

Ujjain rose to prominence as a second capital and a thriving cultural centre.

-

The Iron Pillar inscription in Delhi, attributed to a ruler named ‘Chandra’ (likely Chandragupta II), attests to widespread conquest and influence.

-

He adopted the title Vikramaditya, aligning him with the legendary Shaka conqueror of Ujjain (58–57 BCE).

-

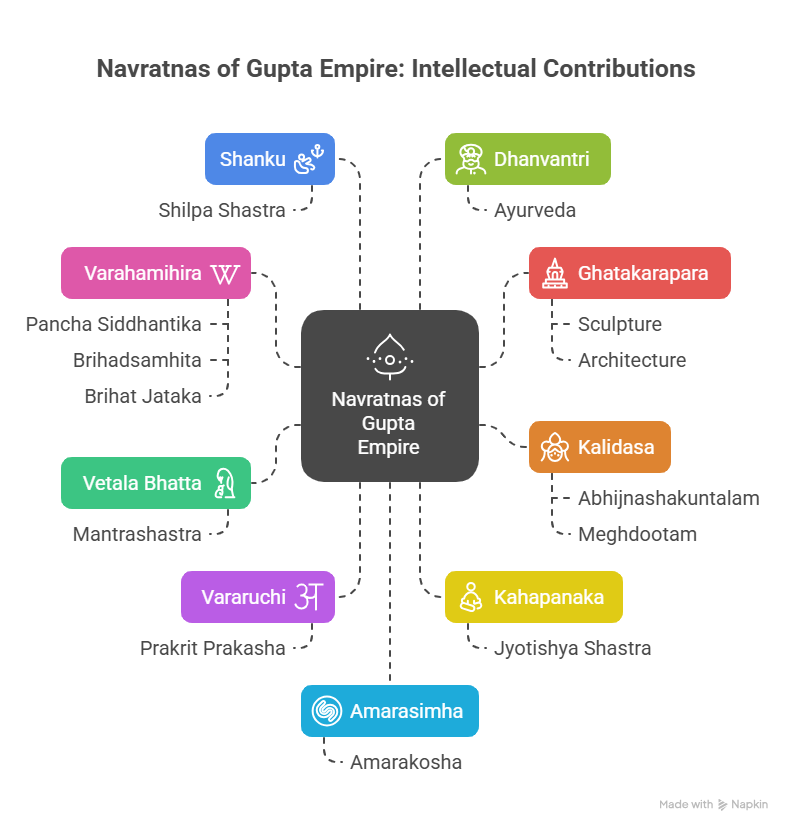

His court hosted celebrated scholars such as Kalidasa, Amarasimha, and Varahamihira, symbolising a golden age of Sanskrit literature, science, and the arts.

-

The Chinese monk Fa-Hien visited India during his reign (c. 399–414 CE) and documented the prosperity, legal system, and religious harmony of Gupta society.

4. Kumaragupta I (c. 415–455 CE)

Kumaragupta I, son of Chandragupta II, enjoyed a lengthy and relatively stable reign. He is credited with maintaining the prosperity and prestige of the empire.

-

He adopted the title Mahendraditya and continued to issue gold and silver coins, reflecting economic strength.

-

He performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, asserting imperial authority and sovereignty.

-

His reign is associated with the establishment of Nalanda University, which later became a renowned centre of Buddhist learning.

-

Towards the end of his rule, the empire encountered threats from the Pushyamitras and the Hunas (White Huns or Hephthalites).

-

Despite these challenges, Kumaragupta I managed to preserve internal stability and imperial continuity.

5. Skandagupta (c. 455–467 CE)

Skandagupta, son of Kumaragupta I, is remembered for his military resistance against foreign invasions and for defending the integrity of the Gupta Empire.

-

He successfully repelled the Huna invasion, a significant external threat during his reign.

-

His victories and administrative decisions are recorded in inscriptions such as the Junagadh rock inscription.

-

His reign, though militarily successful, was marked by economic strain, primarily due to prolonged military campaigns.

-

This is reflected in the debasement of coinage and signs of fiscal difficulty.

-

He also faced internal revolts and regional unrest but managed to maintain Gupta authority during his lifetime.

-

He is widely regarded as the last capable Gupta ruler. After his demise, the empire entered a phase of decline owing to decentralisation and continuous invasions.

1. Administration

1.1 Political Structure and Kingship

- Gupta kings assumed grand titles like Paramēśvara and Mahārājādhirāja to assert supremacy.

- Kingship was hereditary but lacked strict primogeniture, leading to succession conflicts.

- Brahmanas were generously rewarded and portrayed Gupta kings as divine, especially as Vishnu.

- Coins often depicted goddess Lakshmi to reinforce royal divinity.

1.2 Military Organisation

- The army had a standing force and additional troops from feudatories.

- Cavalry and horse archery became dominant.

- Chariots declined in military use.

1.3 Revenue and Taxation

- Land taxes increased, while taxes on trade and commerce declined.

- Tax rates ranged between one-fourth and one-sixth of the produce.

- Villagers supplied goods and were subject to forced labour (vishti) for officials and troops.

1.4 Legal Administration

- Civil and criminal laws were formally separated for the first time.

- Legal decisions were influenced by varna, often guided by Brahmanas.

- Guilds of artisans and merchants had their own internal laws and judicial authority.

1.5 Bureaucracy and Governance

- The bureaucracy was smaller and less centralised than during the Mauryan era.

- Kumaramatyas were key officials, possibly paid in cash.

- Many administrative positions became hereditary and concentrated in a few families.

1.6 Administrative Divisions

- The empire was divided into bhuktis, governed by uparikas.

- Bhuktis were subdivided into vishayas, led by vishayapatis.

- In eastern India, vishayas were further divided into vithis and villages.

1.7 Local and Urban Governance

- Village headmen and elders managed local administration and land records.

- Land transactions required local leadership approval.

- Urban governance involved guilds of merchants, artisans, and bankers.

- Guilds managed internal affairs and enforced their own regulations.

1.8 Feudatory and Land Grant System

- Major parts of the empire were under vassals who paid tribute and offered marital alliances.

- Vassals ruled autonomously under royal charters bearing the Garuda seal.

- Land grants with tax and judicial rights were given to Brahmanas and officials.

- Grantees collected taxes and punished criminals without royal interference.

1.9 Decentralisation

- Fewer officials were needed due to decentralised administration.

- Economic activities were not heavily regulated by the state.

- The political system reflected a semi-feudal structure.

2. Trade and Economy

2.1 Urban and Commercial Prosperity

- Fahien observed that Magadha was prosperous, urbanised, and supported by wealthy patrons.

2.2 Coinage and Currency

- The Guptas issued the highest number of gold coins (dinaras) with standardised weight and size.

- Gold coins depicted kings and their interest in war and art.

- Although lower in purity than Kushan coins, they were used for salaries and land transactions.

- Silver coins were issued after conquering Gujarat, influenced by Western Kshatrapas.

- Limited copper coins indicate lesser monetary circulation among common people compared to Kushan times.

2.3 Decline in Long-distance Trade

- Long-distance trade declined after the Byzantine Empire learned silk production.

- By mid-5th century, international silk demand fell, causing Gujarati weavers to migrate or shift professions.

2.4 Agricultural Changes and Land Ownership

- Land grants to Brahmanas in central India displaced local tribal peasants.

- Tribal peasants were reduced to forced labour in some cases.

- New agricultural lands were developed using advanced techniques introduced by Brahmana landlords.

3. Society

3.1 Caste Hierarchy and Brahmana Supremacy

- Brahmana supremacy increased due to large-scale land grants.

- Guptas, possibly Vaishyas, were elevated to Kshatriya status by Brahmanas.

- Brahmanas legitimised Gupta kings with divine attributes.

- Narada Smriti listed privileges for wealthy Brahmanas.

3.2 Assimilation and Expansion of Caste System

- The caste system expanded by assimilating foreign groups as Kshatriyas.

- Hunas were later included among the 36 Rajput clans.

- Tribal chiefs gained high status, while ordinary tribes were pushed into lower castes.

3.3 Shudras and Economic Roles

- Shudras gained access to epics, Krishna worship, and domestic rituals.

- Economic status of Shudras improved; they became agriculturists by the 7th century.

3.4 Untouchables and Chandalas

- Number of untouchables, especially Chandalas, increased.

- Fa-Hien noted Chandalas lived outside villages and worked with meat.

3.5 Women’s Rights and Social Position

- Women of all varnas were allowed to hear epics and worship Krishna.

- Upper-caste women had no livelihood options or property rights.

- Vaishya and Shudra women had economic freedom through work.

- Stridhana included gifts from both parental and in-law families.

- Katyayana allowed women to sell or mortgage their property and stridhana.

- Daughters were generally denied inheritance of land.

- Niyoga and widow remarriage were banned for higher castes.

- Shudras were allowed niyoga and widow remarriage.

4. Religion

4.1 Buddhism

- Royal patronage of Buddhism declined under the Guptas.

- Fahien noted Buddhism’s presence, but it was less influential than under Ashoka or Kanishka.

- Some monasteries and stupas were built.

- Nalanda emerged as a major Buddhist learning centre.

4.2 Rise of Bhagavatism (Vaishnavism)

- Bhagavatism evolved after the Maurya period, focused on Vishnu worship.

- Vishnu was merged with Narayana, a tribal god, combining Vedic and non-Vedic elements.

- Krishna-Vasudeva, a Vrishni hero, was also linked to Vishnu.

- The Mahabharata was reworked to equate Krishna with Vishnu.

- By 200 BCE, these traditions formed Bhagavatism or Vaishnavism.

- The religion promoted bhakti (devotion) and ahimsa (non-violence), appealing to agrarian societies.

- Worship included rice, sesame offerings, and vegetarianism.

- Attracted foreigners, craftsmen, and traders during Satavahana and Kushan times.

- The Bhagavad Gita opened salvation to women, Vaishyas, and Shudras.

- Vishnu Purana and Vishnu Smriti helped spread Vaishnava beliefs.

- Vaishnavism became more popular than Mahayana Buddhism in Gupta times.

- Vishnu’s avatars explained his role in preserving dharma and social order.

- Supported varna duties and family roles.

- By 6th century, Vishnu was part of the Hindu trinity.

- Bhagavata Purana popularised Vishnu through storytelling.

- Bhagavatagharas (temple halls) were built for reciting his legends.

- Devotional texts like Vishnusahasranama became popular.

4.3 Religious Life and Tolerance

- Some Gupta kings worshipped Shiva; his prominence rose later.

- Temple worship and idol rituals became regular.

- Festivals gained religious meaning and became income sources for priests.

- Guptas tolerated all religions, including Buddhism and Jainism.

- Over time, Buddhism assimilated Hindu practices and neared Brahmanism.

5. Art & Culture

5.1 Patronage and Cultural Support

- The Gupta period, often called a Golden Age, didn’t bring uniform prosperity—some northern towns declined.

- Guptas issued the highest number of gold coins, reflecting wealth.

- Royal and elite classes generously supported art and literature.

- Samudragupta and Chandragupta II were known for their cultural patronage.

- Samudragupta is shown playing the vina on coins.

- Chandragupta II’s court included the Navaratnas (Nine Gems).

5.2 Religious Influence and Sculpture

- Indian art remained largely religious in theme.

- Earlier Buddhist art—pillars, caves, and stupas—was foundational.

- A life-size copper Buddha statue from Sultanganj (now in Birmingham) reflects Gupta craftsmanship.

- Buddha sculptures from Sarnath and Mathura are noted for their grace and expressiveness.

5.3 Ajanta Cave Paintings

- Ajanta cave murals, mostly from Gupta era, depict Buddha’s life and Jatakas.

- These paintings are praised for realism and lasting colour.

- No direct evidence confirms Gupta kings commissioned them.

5.4 Hindu Iconography

- Guptas supported Hindu images, especially of Vishnu and Shiva.

- Hindu art featured a dominant main deity with smaller attendants—mirroring social hierarchy.

5.5 Architecture

- Limited architectural remains survive from the Gupta period.

- Important brick temples: Bhitargaon (Kanpur), Bhitari (Ghazipur), and Deogarh (Jhansi).

- Nalanda University was founded in the 5th century; earliest buildings were brick-made.

6. Literature

6.1 Court Poetry and Drama

- Rise of secular, ornate court poetry in Sanskrit and Prakrit.

- Bhasa wrote 13 Sanskrit plays including Daridracharudatta, adapted later as Mrichchhakatika by Shudraka.

- Mrichchhakatika depicts a Brahmana-courtesan romance.

- Use of the term Yavanika for curtain suggests Greek influence.

6.2 Kalidasa’s Contributions

- Kalidasa, greatest Sanskrit poet, lived in late 4th to early 5th century CE.

- Abhijnanashakuntalam tells the story of Dushyanta and Shakuntala.

- It and the Bhagavad Gita were among the first Indian texts translated into European languages.

6.3 Language and Dialogue

- Gupta dramas were comedies; tragedies were absent.

- Sanskrit was used by upper classes; women and Shudras spoke Prakrit.

6.4 Religious and Epic Literature

- Religious literature flourished.

- The Ramayana and Mahabharata were nearly completed by the 4th century CE.

- Though compiled by Brahmanas, they reflect Kshatriya values.

- Ramayana emphasised family duty and righteousness.

- Mahabharata highlighted that kingship could override kinship.

- The Bhagavad Gita taught action without desire for reward.

6.5 Puranas and Law Literature

- Puranas were compiled to educate people via myths and sermons.

- Several Smritis (law texts) were composed in verse form.

- Commentaries on Smritis began after the Gupta era.

- Sanskrit grammar advanced based on Panini and Patanjali.

- Amarakosha, a Sanskrit lexicon by Amarasimha, was compiled in Chandragupta II’s court.

- Gupta literature preferred verse and ornate style.

- Sanskrit was the official language.

- Early secular literature also emerged despite religious dominance.

7. Science and Technology

7.1 Mathematics and Astronomy

- Aryabhata wrote Aryabhatiya, showing advanced math skills.

- Known for using zero and the decimal system.

- Allahabad inscription (448 AD) indicates decimal system’s use.

7.2 Metallurgy

- Gupta artisans excelled in metallurgy; bronze Buddha statues were notable.

- The Mehrauli Iron Pillar (4th century) resists rust even after 1500 years.

- Western foundries couldn’t replicate such quality until 100 years ago.

Mehrauli iron pillar

7.3 Knowledge Decline

- Unfortunately, the advanced metallurgical knowledge was not passed down.

Fall of the Gupta Empire

Invasions by the Huns

Skandagupta initially defeated the Huns in the early 5th century, but his successors failed to contain their advance. Toramana led successful invasions into western and central India, including areas like Eran near Bhopal. By 485 CE, the Huns had occupied Punjab, Rajasthan, Kashmir, eastern Malwa, and central India. His son Mihirkula, a notorious persecutor of Buddhists (mentioned by Kalhana and Hiuen Tsang), was eventually defeated by Yashodharman of Malwa, Narasimhagupta Baladitya, and the Maukharis. However, this did not revive the Gupta Empire.

Rise of Independent Feudatories

The defeat of Mihirkula by Yashodharman, a former Gupta feudatory, weakened Gupta prestige. Yashodharman claimed control over large parts of northern India and erected 532 victory pillars. Encouraged by his success, other feudatories declared independence in Bihar, Bengal, Gujarat, western Malwa, and other regions. The disappearance of Gupta coins and inscriptions from western Malwa and Saurashtra after Skandagupta indicates a loss of authority.

Economic Weakening and Feudal Expansion

Later Gupta coins had reduced gold content, reflecting economic decline. The scarcity of currency led to payments in land grants to brahmanas and officials, increasing feudalism and weakening central control. The loss of western India reduced foreign trade revenue. The Mandasor inscription shows silk weavers migrating from Gujarat to Malwa in 473 CE and taking up non-productive professions, indicating low demand for luxury goods.

Political Fragmentation after Decline

Following the fall of the Guptas, northern India saw the rise of new powers like the Pushyabhutis of Thanesar, Maukharies of Kanauj, and Maitrakas of Valabhi. In southern India, the Chalukyas and Pallavas rose to power in the Deccan and northern Tamil Nadu.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH