Ethanol Blending: India’s Mixed Blessing

India’s ethanol blending policy boosts energy security and farmer incomes but raises concerns on water use, food security, and consumer costs.

Introduction: Ethanol Blending

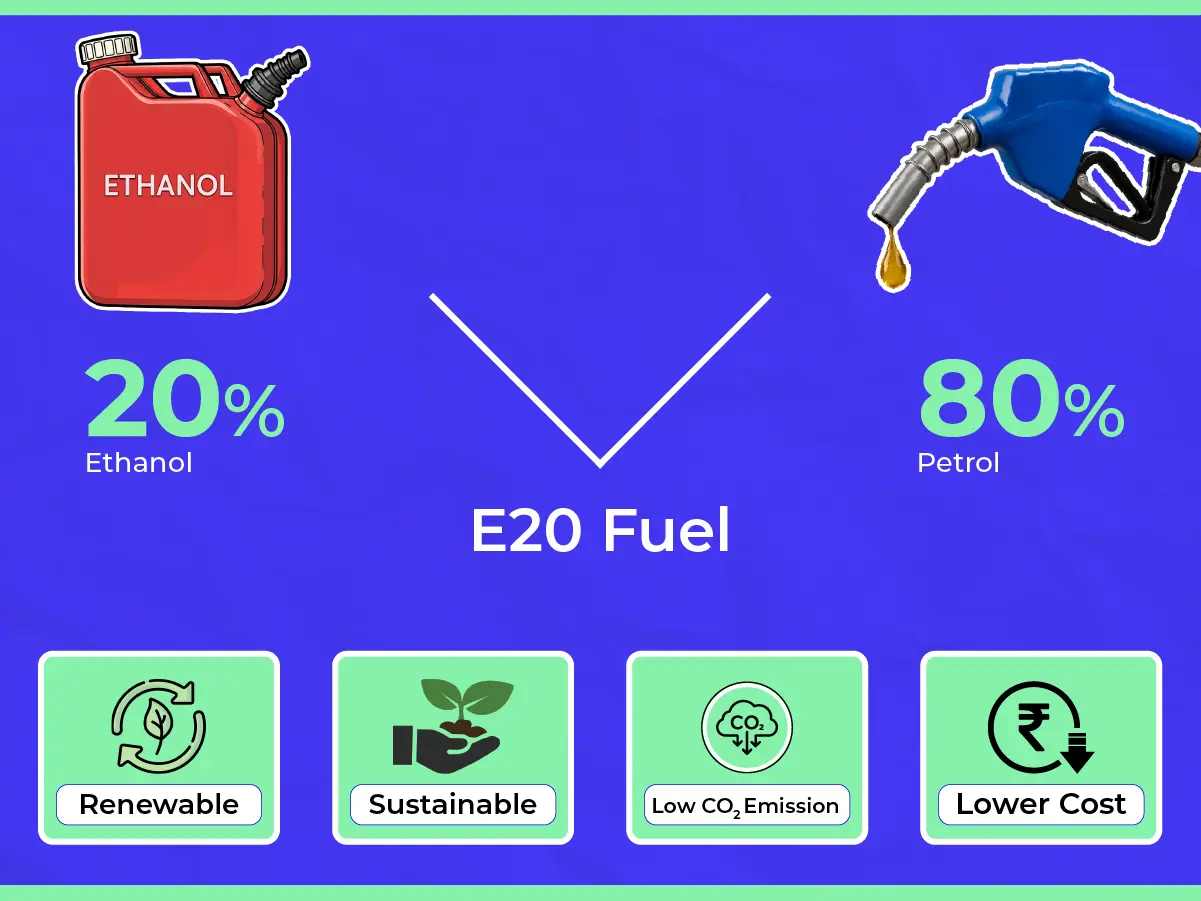

India’s fuel landscape has undergone a striking transformation with the nationwide rollout of petrol blended with 20% ethanol, known as E20. Originally planned for 2030, this target was achieved five years ahead of schedule, an outcome celebrated by policymakers as proof of India’s resolve in tackling climate change, reducing dependence on imported oil, and supporting farmers. Yet beneath this ambitious achievement lies a thorny debate. Drawing on Kunal Shankar S. Hariharan’s critical analysis—“What has been the Impact of Ethanol Blending?” —in The Hindu (August 18, 2025), this essay examines the deeper consequences of ethanol blending for India’s environment, economy, consumers, and future energy pathways. The central thesis here is that while ethanol blending delivers short-term economic and environmental gains, its hidden costs—especially in water use, food security, and consumer welfare—make it an imperfect and unstable solution for India’s long-term sustainability.

Promise of Energy Security

At its core, India’s ethanol blending policy is a response to energy insecurity. For decades, India has been one of the world’s largest importers of crude oil, leaving it exposed to global price shocks. Ethanol, produced locally from sugarcane, maize, and surplus rice, offers a home-grown alternative. By substituting petrol with ethanol, India has saved over ₹1.40 lakh crore in foreign exchange since 2014, strengthening its current account and keeping more money within the national economy. Such savings are not just numbers; they represent schools built, hospitals staffed, and infrastructure developed instead of paying for imported fuel. This has given the government a compelling reason to celebrate ethanol as a triumph of self-reliance.

Farmers at the Heart of the Story

Beyond foreign exchange, ethanol blending has been pitched as a farmer-friendly policy. Sugarcane, one of the main feedstocks for ethanol, has long dominated Indian agriculture, but it often left farmers trapped in cycles of debt due to delayed payments and fluctuating prices. With the government guaranteeing purchases for ethanol production, farmers now enjoy a more stable source of income. Since 2015, payments exceeding ₹1.20 lakh crore have flowed to farmers, creating a sense of security in rural communities. The Fair and Remunerative Price system ensures they receive predictable rates, turning ethanol into a reliable safety net for many. Yet, while this strengthens rural livelihoods, it also raises questions about whether the benefits are spread evenly across India’s diverse farming population.

Consumer Discontent

While farmers and policymakers may cheer, consumers have been less enthusiastic. Surveys reveal that two in three Indian vehicle owners oppose the E20 mandate, with concerns ranging from lower fuel efficiency to increased maintenance costs. Ethanol contains about 30% less energy than petrol, which means cars and bikes running on E20 often deliver fewer kilometres per litre. For households already struggling with rising expenses, this hidden cost feels unfair. Moreover, ethanol is more corrosive than petrol, leading to problems in older vehicles not designed for E20. Reports of engine wear, fuel system failures, and costly repairs have added to public frustration. Although newer vehicles are being built with ethanol compatibility, millions of existing owners feel left behind, fuelling resentment against what they see as a forced transition.

Environmental Dilemma

One of the government’s strongest claims is that ethanol blending helps fight climate change. Official figures suggest that India has avoided 700 lakh tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions thanks to E20, a figure used proudly in international climate negotiations. However, the picture is far more complicated. Ethanol’s “greenness” depends heavily on how it is produced, and in India, most of it comes from sugarcane—a notoriously water-thirsty crop. Producing one tonne of sugarcane can consume up to 70 tonnes of water, often drawn from groundwater reserves in already drought-prone regions like Maharashtra. The Central Groundwater Board has linked falling aquifer levels directly to sugarcane farming, raising fears of long-term water crises. Thus, while ethanol may reduce emissions from car exhausts, its cultivation risks undermining India’s water security.

Soil and Land Under Pressure

The environmental challenge does not stop at water. Intensive sugarcane cultivation often relies on heavy fertiliser and pesticide use, leading to soil degradation and chemical runoff into rivers. The Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas of India 2021 revealed that nearly 30% of India’s land shows signs of degradation—a figure worsened by water-hungry crops. While government attempts to diversify ethanol production towards rice and maize offer some relief, these too create problems. Diverting food grains for fuel risks raising prices and straining food security, especially when millions of Indians still face undernutrition. In fact, India was recently forced to import corn at record levels to make up for ethanol-driven shortages, showing how one problem begets another.

Who Really Benefits?

On paper, ethanol blending looks like an economic win: reduced oil imports, boosted farmer incomes, and expanded rural jobs. But the distribution of these gains is uneven. Oil marketing companies, such as IOC and BPCL, have seen soaring profits and paid record dividends to the government. Yet, retail petrol prices have fallen by only 2%, leaving consumers wondering why they bear the costs without reaping the rewards. Critics argue that much of the wealth generated by ethanol blending has stayed with corporations and the state, rather than being passed down to ordinary citizens. This imbalance risks eroding public trust in what is presented as a “people’s policy.”

Trade Pressures and International Friction

India’s ethanol strategy has not gone unnoticed abroad. The United States has pushed India to relax restrictions on ethanol imports, calling them trade barriers. Opening the market could provide cheaper ethanol, but it would also threaten India’s domestic producers and farmers who now depend on the government-backed system. This puts India in a delicate position: balancing international trade obligations with the need to protect its rural economy. Any misstep could destabilise the fragile equilibrium built around ethanol blending, creating ripple effects across agriculture and industry.

Electric Vehicle Crossroads

Perhaps the greatest challenge to ethanol blending is not foreign but domestic: India’s ambition to adopt electric vehicles (EVs). While E20 has reduced emissions, EVs powered by renewable energy offer a far deeper cut in transport-related pollution. Yet India’s EV adoption remains sluggish, with only 7.6% of vehicles sold in 2024 being electric. Scaling up to the 30% target by 2030 will require massive investments in charging infrastructure, battery technology, and renewable power. Moreover, India faces a critical shortage of rare earth elements—metals essential for EV batteries and motors—most of which are controlled by China. This creates a supply risk that threatens to slow the EV transition. The government thus faces a crossroads: should it keep investing heavily in ethanol blending, or pivot more decisively towards EVs as the ultimate green solution?

A Policy of Trade-offs

Ethanol blending, then, emerges as a story of trade-offs. It delivers genuine wins in energy security, farmer income, and emission reduction, but it also creates hidden costs in consumer pockets, water resources, and soil health. It strengthens rural economies but risks raising food prices. It positions India as a climate leader but also locks the country into an environmentally risky agricultural model. In essence, E20 is both a solution and a problem—a bridge that could either lead to a cleaner future or collapse under its own contradictions.

Conclusion

India’s rapid achievement of E20 ethanol blending is both impressive and troubling. It shows what determined policymaking can achieve, but it also exposes the limits of quick-fix solutions in the face of complex challenges like climate change, food security, and technological transition. The future of ethanol blending will depend on whether policymakers can make it more sustainable: by promoting water-smart agriculture, diversifying feedstocks responsibly, compensating consumers fairly, and ensuring it does not distract from the rise of electric vehicles. Only then can ethanol blending move from being a “mixed blessing” to a truly sustainable cornerstone of India’s energy strategy. For now, it remains a remarkable milestone shadowed by deep uncertainties—a victory that may yet prove fragile.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH