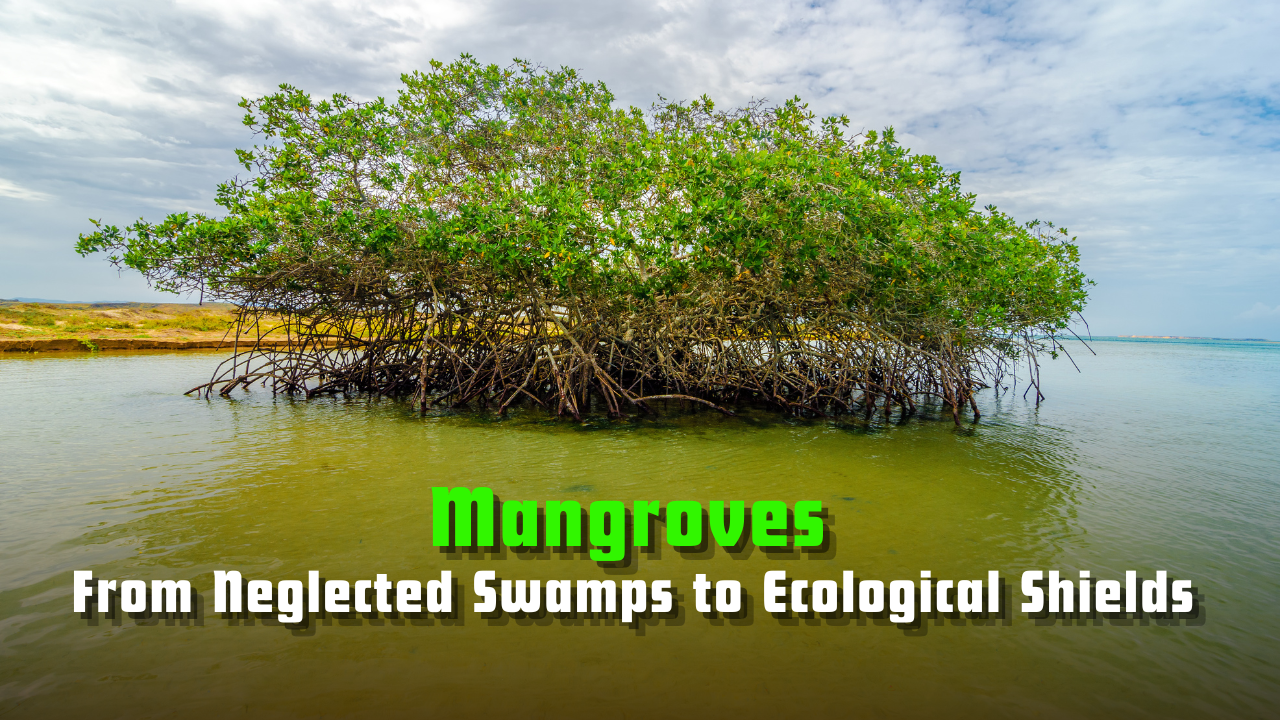

Mangroves: From Neglected Swamps to Ecological Shields

Discover how M.S. Swaminathan transformed mangroves from neglected swamps to vital ecological shields, shaping global conservation and climate resilience.

Introduction: Mangroves

Until the late 1980s, mangroves were largely dismissed as muddy, mosquito-ridden wastelands by most people—except those who depended on them for a living. For coastal communities, these salt-loving forests were invaluable, providing fish, crabs, and wood, as well as sheltering villages from storms. Yet, the wider world overlooked their importance, and mangroves were cleared for agriculture, salt pans, and buildings. Today, “mangroves” has become a global buzzword, recognised for their crucial role in climate adaptation, disaster prevention, and environmental health. This transformation is closely linked to the life and vision of M.S. Swaminathan, the pioneering scientist whose work made mangroves matter worldwide, as detailed by Selvam Vaithilingam in “The Scientist Who Made ‘Mangroves’ a Buzzword” (The Hindu, July 26, 2025).

Swaminathan’s Vision for Mangroves

For generations, only those who lived near mangroves understood their value. However, a dramatic shift occurred at the end of the 20th century. In 1989, at the Climate Change and Human Responses conference in Tokyo, M.S. Swaminathan, already celebrated for India’s Green Revolution, issued a warning: climate change would bring higher sea levels, cause widespread salinisation, and threaten the livelihoods of millions. He argued that mangroves were not just trees, but nature’s first line of defence against these dangers. His ideas convinced the global scientific community and policymakers to rethink mangrove conservation.

Swaminathan’s approach was both scientific and practical. He proposed the immediate protection and restoration of mangrove wetlands to buffer coastlines from storms and to trap large amounts of carbon dioxide, helping to fight global warming. He was also the first to suggest using mangrove genetic material to develop crops that could survive in increasingly salty soils—a forward-looking idea as climate change threatens food security in low-lying regions.

Building Global Infrastructure for Mangrove Conservation

Swaminathan was not just a thinker; he was a builder of institutions. His efforts led to the creation of the International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems (ISME) in Okinawa, Japan, in 1990, where he served as the founding President. Under his guidance, ISME united scientists, policymakers, and communities from around the world. The society launched research programmes, organised training workshops, and published resources such as the World Mangrove Atlas. These actions helped rebrand mangroves—from neglected marshlands to “ecological superheroes” vital for disaster risk reduction, biodiversity, and local economies.

A major achievement was the drafting of the Charter for Mangroves, which became part of the United Nations’ World Charter for Nature in 1992. This step brought mangroves onto the world stage, shaping international conservation policy. ISME’s work also included training managers, promoting practical conservation methods, and running public awareness campaigns.

Another of Swaminathan’s breakthroughs was the Global Mangrove Database and Information System (GLOMIS), which became the main source for mangrove research, species data, and conservation efforts. In 1992, Swaminathan guided surveys of 23 mangrove sites across Asia and Oceania, leading to the creation of Mangrove Genetic Resource Centres. These centres are now managed by governments as protected areas, preserving rare mangrove species and genetic diversity for the future.

Revolutionising Mangrove Management in India

India’s journey with mangroves has been long and difficult. During British rule, and for decades after, mangroves were often cleared to make way for farming and settlements—a practice known as clear-felling. These actions devastated vast areas of vital coastal forest, especially in the Sundarbans. Management plans made by colonial and later state authorities often failed to restore lost forests, and local communities were wrongly blamed for the degradation.

Under Swaminathan’s guidance, the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) introduced participatory science, working directly with local people and state forest departments. Their research proved that it was not the villagers, but poor management and environmental changes—especially the loss of natural water channels due to clear-felling—that led to dying mangroves.

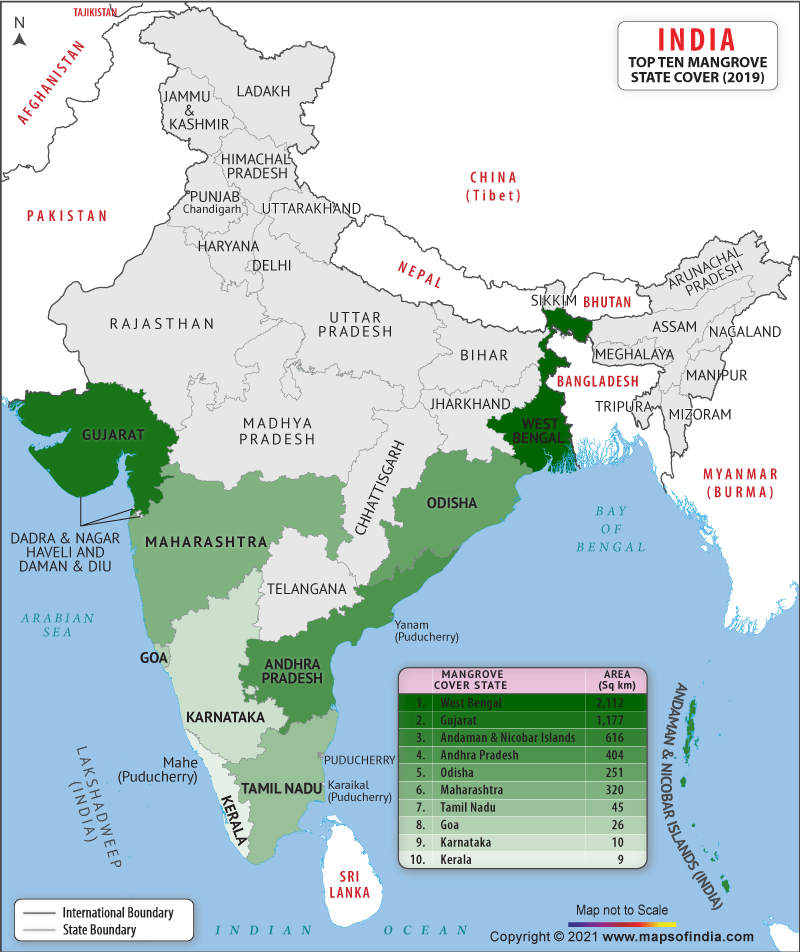

Swaminathan’s team devised the “fishbone canal method,” a way of restoring mangroves by digging small, branching channels to mimic natural tidal flows. This innovative technique brought degraded mangrove forests back to life in states such as Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, and West Bengal. Its success led to the national adoption of Joint Mangrove Management (JMM), where scientists, officials, and villagers worked together. By 2000, this programme became the national model for mangrove restoration. The government invested more in protecting and expanding mangroves, especially after they proved their worth in natural disasters.

Nature’s Shield: Mangroves in Action During Disasters

The value of mangroves as natural barriers was made tragically clear during major disasters. When the Odisha super cyclone struck in 1999, and again during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, areas protected by healthy mangrove belts suffered less damage, losing fewer lives and less property compared to places without mangroves. These forests absorb the force of storm surges, reduce flooding, and slow down destructive waves. After these disasters, both Indian and international agencies increased their investment in mangrove restoration, further cementing their importance in disaster risk management and climate change adaptation.

The Rise in Mangrove Cover

The results of Swaminathan’s efforts are measurable. According to the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2023, mangrove forests now cover 4,991.68 km², accounting for 0.15% of India’s total area. Between 2019 and 2023 alone, mangrove coverage grew by 16.68 km²—a sign of successful restoration and growing awareness. India’s progress stands as a model for other countries with threatened coastal forests, demonstrating the power of combining science, strong laws, and community involvement.

The Challenges Ahead

Despite this success, mangroves still face serious threats: unchecked coastal development, pollution, illegal logging, and the effects of a rapidly changing climate. Sometimes, government policies remain weak or local communities are left out of decision-making. To secure a future for mangroves, the path forward is clear:

- Strengthen and enforce laws to prevent mangrove destruction.

- Expand community participation, learning from successful JMM projects.

- Invest in scientific research on how mangroves adapt to new challenges and how their genes might help agriculture.

- Foster global cooperation through networks like ISME and databases like GLOMIS, sharing knowledge and resources across borders.

Conclusion

M.S. Swaminathan’s life’s work brought mangroves out of the shadows, showing the world that these unique coastal forests are not useless wastelands, but priceless ecosystems central to humanity’s survival. By blending rigorous science, international leadership, and deep respect for local knowledge, he sparked a global movement for mangrove conservation. The term “mangrove” is now a symbol of resilience, hope, and the ongoing struggle for a sustainable future.

As climate change intensifies, Swaminathan’s lessons are more urgent than ever. Mangroves must be protected and restored, not just as green belts on a map, but as living guardians of our coasts and communities. Every July 26, on World Mangrove Day, we are reminded of how far we have come—and how much further we must go. For today’s students and future leaders, Swaminathan’s story is a call to action: let us value, protect, and cherish the hidden treasures of our coasts for generations to come.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH