Font size:

Print

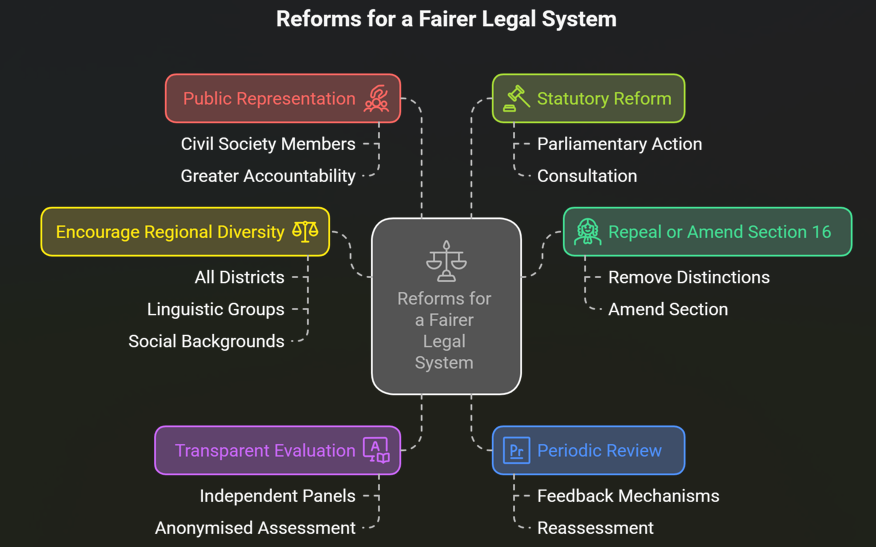

Practising equality in constitutional courts

Practising Equality in Constitutional Courts: Rethinking the Senior Advocate Designation System in India

Context: Recently, the Supreme Court of India decided to refix the methodology and the criteria for designating lawyers as senior lawyers.

What is the issue surrounding the designation of senior advocates in India?

When and how did this controversy gain judicial attention?

The controversy was addressed notably in three judgments:

- Indira Jaising v. Supreme Court of India (2017) – Supreme Court laid down guidelines for designating senior advocates.

- National Lawyers’ Campaign v. Supreme Court (2017) – Challenged Section 16 as unconstitutional.

- Jitender @ Kalla v. State (2025) – Revisited the issue and criticised the subjectivity of the existing point-based system but upheld the classification.

- The issue revolves around the systemic inequality within the legal profession, particularly regarding the designation of ‘senior advocates’ under Section 16 of the Advocates Act, 1961.

- This provision allows constitutional courts to designate lawyers as senior advocates based on ability, standing, or special knowledge.

- While intended to recognise merit, it has resulted in hierarchical divisions within the Bar and perpetuated elitism, marginalising many deserving lawyers.

Why is this issue significant for constitutional democracy in India?

- Public Character of the Legal Profession: The legal profession plays a vital public role, and internal disparities affect judicial access and the fairness of democratic processes.

- Concentration of Legal Power: The dominance of a few ‘star lawyers’ leads to a legal plutocracy, limiting access to justice for the majority and creating an uneven playing field in the courts.

- Constitutional Erosion and Intellectual Exclusion: Such inequality undermines the egalitarian principles enshrined in Articles 14 (Right to Equality) and 39A (Equal Justice and Free Legal Aid) of the Constitution, fostering intellectual apartheid within legal discourse.

Who is affected by the current system of senior advocate designation?

- Marginalised and underrepresented lawyers: Including those from non-metropolitan areas, lower socio-economic backgrounds, women, and Dalits.

- Young and first-generation advocates: Often lacking elite mentorship or visibility.

- General public and litigants: Whose cases are sometimes filtered through the lens of a few “elite” lawyers, skewing access to judicial representation.

How has the Supreme Court responded to criticisms of inequality in this system?

Where does this practice come from and how does it compare globally?

Section 16 of the Advocates Act, 1961 is the statutory origin of this classification.

Globally:

- U.S.: While there’s no formal senior designation, elite lawyers dominate Supreme Court access.

- Other countries: such as Nigeria, Ireland, Australia, and Singapore have similar systems of classification.

- Legality Upheld: The Court has upheld the constitutionality of classification under Section 16, rejecting claims that the dual class system of advocates is unconstitutional.

- Limited Reforms Suggested: While recognising flaws in transparency and criteria, the Court only recommended peripheral reforms like revising High Court rules.

- Subjectivity Overlooked: In the Jitender Case (2025), the Court admitted the point-based system is “highly subjective” but paradoxically allowed its continuation without referring broader constitutional issues to a Constitution Bench.

What are the core constitutional and democratic concerns?

- Violation of Article 14: Arbitrary classification creates unequal treatment among equals.

- Lack of transparency and accountability: Designation often depends on subjective perception and elite networking, not merit.

- Erosion of diversity and representative character of the Bar: Women, minorities, and rural lawyers are often overlooked.

- Risk of commercialisation: Legal practice veers toward a corporatised model, similar to the U.S., undermining public interest litigation.