Font size:

Print

GDP Base Year Revision: A Strategic Move to Boost India’s Global Credibility

GDP Base Year Revision: A Bold Step Toward Accurate Economic Ranking for India

Context (GDP): The National Statistical Office (NSO) has decided to shift the base year for India’s national accounts from 2011‑12 to 2022‑23.

How have earlier base‑year revisions unfolded, and why did the 2015 rebasing spark controversy?

- Since the first official series in 1951, India has rebased seven times (1967, 1978, 1988, 1999, 2006, 2010 and 2015).

- Each exercise broadened coverage, plugged data gaps and adopted the latest UN System of National Accounts (SNA) guidelines.

- The 2015 shift to 2011‑12 introduced corporate filings from the MCA‑21 database and a new supply‑use framework.

- While applauded for richer coverage, critics—including former CEA Arvind Subramanian and economist R. Nagaraj—argued that the new methods overstated growth, especially in manufacturing, by 1–2.5 percentage points.

More in News: The fully back‑cast series, covering GDP, Gross Value Added (GVA) and allied macro indicators, is scheduled for public release on 27 February 2026.

- Parallel exercises will align the base year for the Index of Industrial Production (IIP) and Consumer Price Index (CPI) to 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 respectively, ensuring methodological consistency across key high‑frequency datasets.

What is the rationale behind GDP base‑year revision?

- Price structure: A fresh base anchors the constant‑price series to a recent year’s relative prices, yielding more accurate “real” growth estimates.

- Economic structure: It captures structural shifts—for India that means the rise of digital services, platform‑based gig work, renewable energy and complex supply chains often absent from older datasets.

- Data quality: Each rebasing absorbs new surveys (e.g., Periodic Labour Force Survey), improved administrative data (GST, e‑Way bills), and satellite accounts (environment, digital economy), tightening the statistical net.

How do regular GDP revisions help policy and markets?

- Sharper policy targeting: Reliable sectoral weights guide fiscal outlays, monetary calibration and PLI‑style industrial incentives.

- Investor confidence: Global funds benchmark asset allocations to credible macro numbers; mis‑measurement elevates risk premia.

- Inter‑state comparability: States re‑estimate their GSDP off the national base, influencing Finance‑Commission transfers and borrowing limits.

- Academic research: Updated series underpin poverty, productivity and inequality studies, affecting social‑sector programme design.

Why was the base year not changed five years after 2011‑12?

What is a “base year” and why must it be revised periodically?

- The base year is the reference year whose price‑quantity structure is fixed at 100 and against which volume or “real” growth is measured.

- Over time, relative prices, consumption baskets and production technologies drift, making old weights misleading. Best practice—enshrined in the UN‑SNA and endorsed by India’s National Statistical Commission—recommends rebasing every five years.

- 2017‑18 had been earmarked, but key input surveys were derailed:The Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES 2017‑18) was withheld over data‑quality concerns.The first Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS 2017‑18) showed a 45‑year‑high unemployment rate, triggering a lengthy validation.

- Concurrent shocks—demonetisation (Nov 2016) and GST rollout (Jul 2017)—made 2017‑18 atypical, undermining its suitability as a “normal” base.

- Subsequent pandemic disruptions (2020‑22) further delayed the exercise.

What unique challenges does the 2026 rebasing face?

- Data gaps:Census 2021 is yet to be completed, limiting granular demographic benchmarks.

- Informal‑sector mapping relies on older NSS rounds; integrating gig‑economy platforms demands new survey frames.

- Methodological balance:Leveraging big administrative datasets (GST, FASTag, Aadhaar‑linked farm records) improves coverage but risks double‑counting and demands robust de‑duplication algorithms.

- Price volatility:Post‑Covid commodity swings and green‑transition subsidies distort deflators; statisticians must choose representative price indices carefully.

- International alignment:India plans to migrate further towards SNA 2008/2019 modules (e.g., delineating “intellectual‑property products”); harmonising with legacy series will be technically demanding.

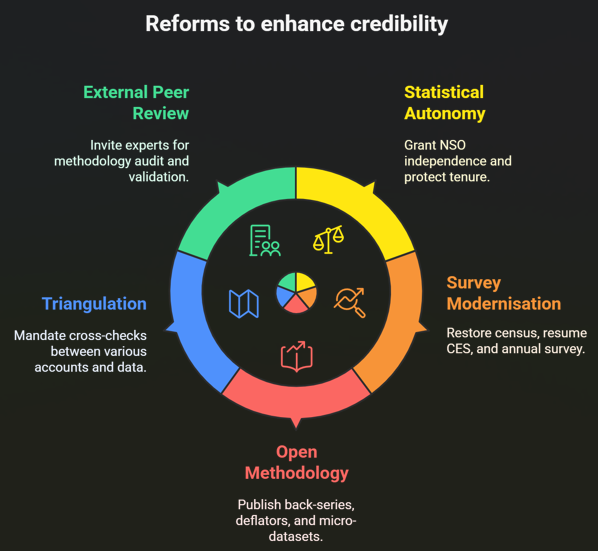

- Transparency test:Given past scepticism, the Advisory Committee’s decisions on sources and deflators will be scrutinised by credit‑rating agencies and multilateral lenders.

Why is this revision crucial for India’s global standing?

- Size transition: By 2026 India is expected to surpass Germany and Japan to become the world’s third‑largest economy (nominal GDP); an accurate baseline is critical to that milestone.

- Capital flows: Portfolio and FDI investors price assets off growth expectations; credible data can lower India’s cost of capital.

- Policy leadership: As a G‑20 heavyweight and Quad/WTO negotiator, India’s advocacy on climate finance, digital trade and WTO reform hinges on trusted macro‑metrics.

- Reputation repair: A transparent, technically sound rebasing offers a chance to lay to rest the 2015 over‑estimation debate and demonstrate statistical independence.

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel for more Valuable Content – TheStudyias

Download the App to Subscribe to our Courses – Thestudyias

The Source’s Authority and Ownership of the Article is Claimed By THE STUDY IAS BY MANIKANT SINGH